Like cheetahs, fast bullets look the part, but speed alone doesn’t kill and reach unused is pointless.

I shed my pack, slid my arm through the sling and crawled ahead. Only tines showed. The weeds were noisy. Each advancing inch carried risk. Belly to earth, I settled the crosswire above the antler. This close in, with dead air, my scent would reach him soon. “Hey, buck,” I said softly. An ear tip twitched. Again, and its head swiveled. I raised my foot, gently let it fall. The reticle quivered. The buck rose fluidly, one heartbeat from gone, collapsing at the report. On the treeless prairie, whose bleached grass bled to sagging November skies, my bullet had traveled perhaps a dozen steps.

“The last desert ram I shot was not over 30 yards away,” wrote Jack O’Connor, “and the best Dall I have ever taken was maybe about 40 yards from the muzzle …” He allowed that most of the sheep he’d shot probably fell inside 150 yards. Like mid-continent’s prairie, northern sheep country yields much to the hunter’s glass. That killing shots would come close in such environs might seem odd. But long pokes are seldom needed. On my first Alaskan sheep hunt, I carried an iron-sighted Springfield, downing a Dall’s ram at 70 yards on bald shale. Even for sharp-eyed pronghorns on featureless flats, I’ve found lever rifles with aperture sights adequate. The utility of such rifles in eastern whitetail cover is obvious.

Still, the focus of cartridge and bullet design now is on flatter flight and more precise hits at long range. Powerful optics make accurate aim possible beyond the practical reach of traditional “deer rifles,” with their blunt bullets at modest speeds. Sounds like progress.

But wait a minute.

Indeed, the 19th-century shift from patched round balls to conical bullets was a step forward for hunters using muzzleloaders. The ratio of weight to frontal area was higher for conicals, so they fought drag better. They packed more momentum and penetrated deeper.

The march of breech-loading rifles into the 1860s, and the advent of smokeless powder 30 years later, had little effect on bullet shape. Primitive optical sights weren’t reliable enough for hunters. Lethal reach was primarily determined by how well hunters and soldiers could aim with iron sights. But smokeless fuel forced changes in bullet construction, as it sent naked lead bullets so fast they stripped in the rifling and left lead smears in the bore. The U.S. Army tried tin plating but found it could “cold solder” to the case mouth, bumping pressures. One bullet left wearing the neck! Cupro-nickel jackets (60/40 copper/nickel) were better. By 1922, Western Cartridge had a jacket alloy of 90 percent copper, 8 percent zinc, 2 percent tin. Called Lubaloy, this “gilding metal” blessed Western’s Palma Match cartridges that year. Now, most bullet makers use jackets comprising 95 percent copper and 5 percent zinc.

Improved propellants and more dependable optical sights with jackets that endured greater bore friction pushed the development of frothy cartridges than bullets that held their velocity better at a distance. The first cartridge in 1898 Mausers was a smokeless 8mm for the 1888 Commission rifle, which had little Mauser influence. Officially, the 7.9×57 or 7.9x57J (correctly, I; in German, these letters can interchange) sent a 227-grain .318 bullet at 2,100 fps. Germany soon had a more potent round for the stronger 1898. The 8×57, with a 154-grain pointed .323 bullet at 2,870 fps, appeared in 1905. Designated 7.9x57IS and 8x57IS, the 8×57 would see Germany through WWII. A Lange Visier rear sight could be set for dead-on aim to 2,000 yards. This 8mm inspired the U.S. Army to swap a blunt bullet for a spitzer in the .30-06.

Round- and flat-nose bullets remained standard in cartridges for tube-fed Winchester and Marlin lever rifles, as primers resting on pointed bullets in the magazine could detonate when the rifle recoiled.

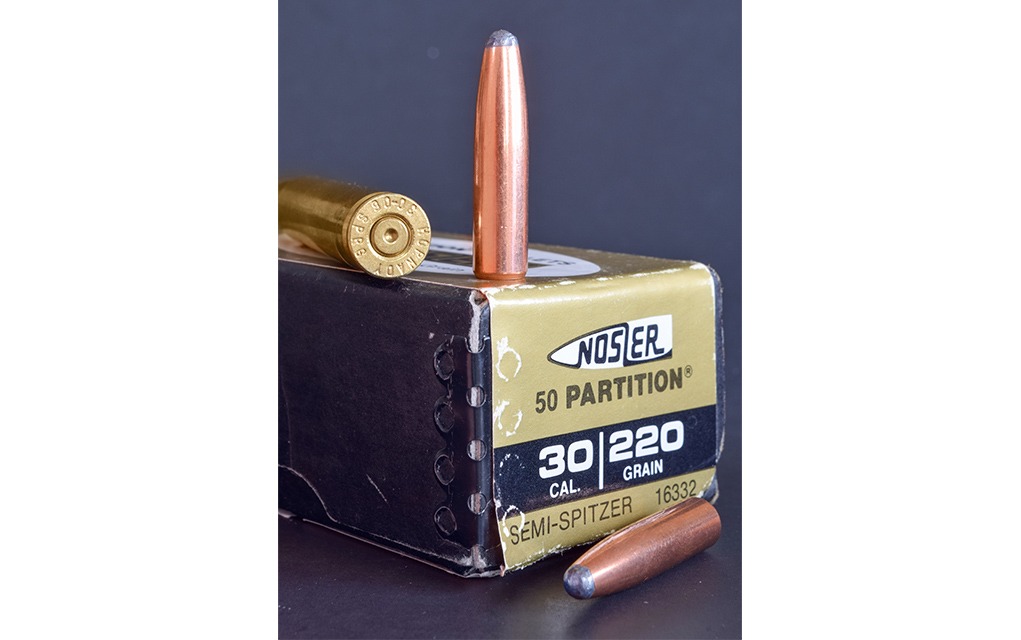

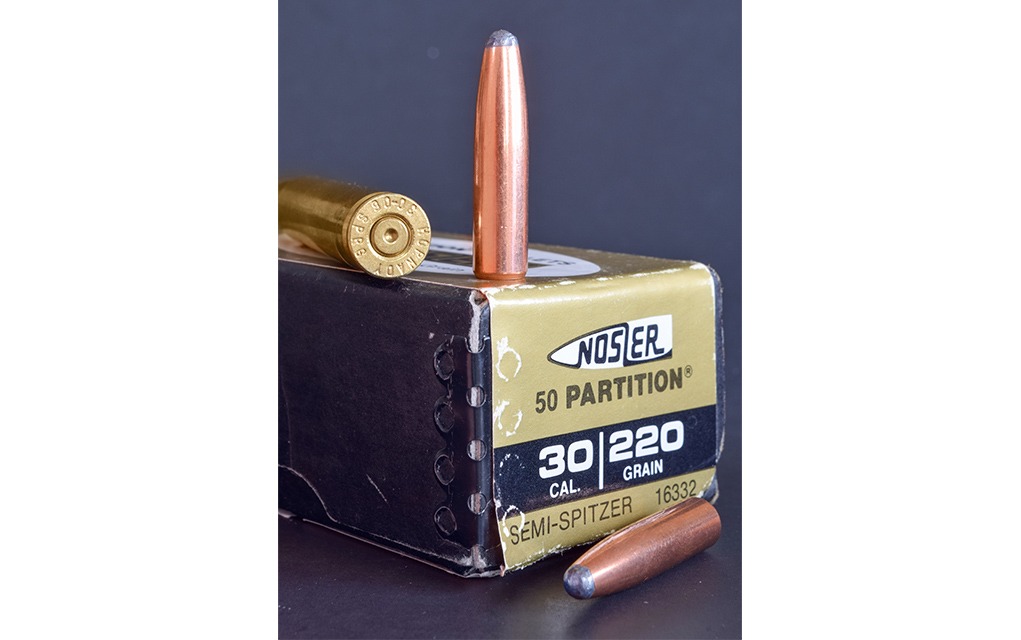

For soldiers firing full-jacket bullets, the shift to spitzers dramatically increased effective range. But hunters also had to consider how an expanding bullet behaved after winning its battle with air. On a 1946 moose hunt, John Nosler famously failed to drop a mud-spackled bull with his .300 H&H. When at last the bull succumbed, Nosler found his first bullet had fragmented on entry. With machine-shop savvy from rebuilding automobile engines, he designed a two-part bullet with a web of jacket material between nose and heel. The heel powered on as a solid if the nose failed, ensuring penetration. Next season, John and his pal Clarence Purdie handily killed moose with this homemade bullet. The Nosler Partition Bullet Company was soon birthed in Ashland, Oregon. (Incidentally, in 1915, Charles Newton had designed a partitioned bullet. Poor timing doomed it and Newton’s other worthy projects.)

Also, to improve bullet performance in tough game, Bill Steiger soldered a thick, ductile copper jacket to a lead core. In 1964, he founded Bitterroot Bonded Core Bullets in Lewiston, Idaho—where he also wrote Speer’s first five loading manuals. Years later, IBM executive Jack Carter was drawn to bonded bullets when, in Africa, a Cape buffalo absorbed several shots from his .375. He designed a bullet with a thick copper heel and a bonded nose. Its center of gravity lay farther forward than that of a pointed lead-core bullet. He sold his Trophy Bonded Bear Claw bullet to Federal, which began loading it in 1992. Next year, Federal brought production in-house, changing jacket material from copper to 90/10 gilding metal, which Nosler had used for Partition bullets turned on screw machines until 1970.

Geoff McDonald’s rural Australia shop chugs out Woodleigh Weldcore bullets, bonding 90/10 jackets to lead cores. His are big-bore bullets, solid and soft-nose, for traditional dangerous-game rounds. In the early 1980s, Lee Reed improved Nosler’s Partition by bonding its front section. Swift’s A-Frame resulted. Since then, all major ammunition makers have cataloged bonded-bullet loads (Federal, Norma and Kynoch have featured Woodleighs). Their common purpose: deep penetration and dependable upset in tough game, with at least 90 percent weight retention.

None of these bullets had Pinocchio noses. Nobody at the time seemed to care.

The Era of the Sharp Polymer Tip followed a preoccupation with long-range hits, first on paper and steel targets, then on game. Not to say testing the reach of rifles, ammunition and shooters is new: In 1874, Remington’s L.L. Hepburn designed a Rolling Block rifle to beat the Irish champs in a long-range match. Each team would comprise six men, shooting three rounds at 800, 900 and 1,000 yards, 15 shots per round. A young National Rifle Association, with the cities of New York and Brooklyn, each put up $5,000 for a venue on Long Island’s Creed’s Farm, provided by the State of New York. In September, the Irish team lost to the Americans firing 550-grain bullets from their .44-90s. Sharps dropping-block rifles contributed to the winning score: 934 to 931, with one Irish crossfire. No sharp bullets.

A century and a half later, shooters prop heavy-barreled bolt-actions on bipods and read mirage through riflescopes the diameter of truck axles, with magnifications once reserved for spotting scopes. Once a rare stunt, hitting generous targets at a mile (1,700 yards) has become the first step toward a two-mile attempt. Such efforts have given rise to long-range bullets with high ballistic coefficients (BCs).

BC is a number representing a bullet’s ability to cleave the air. It incorporates bullet weight, shape and diameter. Change any of these variables, and you change the BC. Long, sleek aerodynamic bullets have high BCs. Hornady’s 143-grain 6.5mm ELD-X is .623. A corresponding 7mm bullet (162 grains) comes in at .631. Most traditional pointed soft-nose game bullets hover in the .380 to .490 range. These are “G1” figures, computed using a “standard bullet” (for comparisons) of a century ago. Ballisticians have since adopted a standard bullet better resembling the sleek, long-nose boat-tails popular now. Result: the “G7” BC. A bullet’s G7 BC is lower than its G1 BC. The values are equally useful. Think of any object that can be measured in inches or centimeters. Comparisons are valid if the units are the same.

Lost in this race to higher BCs and hits at more extended ranges is bullet performance on game.

The soft-nose struck audibly. With a bellow, the buffalo spun toward me. Through the dust, I sent a solid. The bull absorbed it, lunged off course, then crashed to earth as another solid broke its neck.

The three 9.3×62 bullets ending my Namibian hunt had round noses. For much of the world’s big game hunting, blunt is still best. A blunt bullet is heavier than a pointed bullet of the same length, as nose taper exacts a cost in material. The only way to add weight to a pointed bullet is to make it longer, bringing challenges from the rifle’s action, magazine and rifling twist.

Bullets heavy for their diameter have a high sectional density (SD). In a number, SD is the bullet’s mass (weight) divided by its diameter squared: M/D2. Alternatively, it is mass divided by cross-sectional area: M/R2 x pi. (Yes, the results differ, but by a constant ratio).

For any given weight, the slimmer a bullet, the higher its SD. The longer a bullet, the higher its SD, if the nose shape is the same for any given diameter.

What is a “high” SD? My arbitrary threshold is .300. These bullets meet it (see Table 1).

TABLE 1

| BULLET DIAMETER/WEIGHT | SECTIONAL DENSITY SD (M/D2) |

| .264 (6.5mm): 160 gr. | .328 |

| .284 (7mm): 175 gr. | .310 |

| .308: 200 gr. | .301 |

| .308: 220 gr. | .331 |

| .311 (.303 British): 215 gr. | .316 |

| .323 (8mm): 220 gr. | .301 |

| .338: 250 gr. | .313 |

| .338: 275 gr. | .348 |

| .358: 275 gr. | .306 |

| .366 (9.3mm): 286 gr. | .305 |

| .366 (9.3mm): 300 gr. | .320 |

| .375: 300 gr. | .305 |

| .416: 400 gr. | .330 |

| .458: 500 gr. | .341 |

While even round-nose and semi-spitzer bullets fly flatter and carry energy more efficiently than missiles shaped like soup cans, a tapered nose isn’t necessary. Before vehicles entered Kenya’s Serengeti Plain, a Dutchman named Fourrie guided John A. Hunter’s safari toward Ngorongoro Crater. Fourrie was a resourceful fellow. When hunters in the party rashly shot their way out of solid bullets, Fourrie reversed soft points in their cases. These flat-nose “solids” drove deep and broke big bones in heavy game.

Skeptics sneer that as soon as round- or flat-nose bullets leave the muzzle, they “head for dirt.” In fact, many blunt bullets with SDs of .300 fly flat enough for 200-yard zeros. For some, point-blank range (farthest at which a bullet stays within 3 vertical inches of sightline) exceeds 240 yards. These examples are from an old B&L list (See Table 2).

TABLE 2

| CARTRIDGE/WEIGHT | ZERO RANGE (YARDS) | MAXIMUM POINT-BLANK RANGE (YARDS) |

| 6.5×54 M-S, 156 gr. | 206 | 242 |

| 6.5×55 Swedish, 156 gr. | 209 | 245 |

| 7×57 Mauser, 175 gr. | 201 | 235 |

| .280 Remington, 165 gr. | 228 | 266 |

| .30-40 Krag, 220 gr. | 185 | 217 |

| .300 Savage, 180 gr. | 190 | 222 |

| .308 Winchester, 200 gr. | 203 | 238 |

| .30-06, 220 gr. | 197 | 230 |

| .300 H&H Mag., 220 gr. | 217 | 254 |

| .303 British, 215 gr. | 182 | 213 |

| .338 Win. Mag., 250 gr. | 221 | 259 |

| .348 Winchester, 250 gr. | 186 | 216 |

| .358 Winchester, 250 gr. | 187 | 219 |

| .375 H&H Mag., 300 gr. | 226 | 264 |

Early in the 20th century, the 6.5×45 M-S, 7×57 Mauser and .303 British served famous explorers and hunters like Charles Sheldon, F.C. Selous, Jim Corbett and W.D.M. Bell on dangerous game. While speedy bullets with high BCs can kill at eye-popping distances, heavy round-noses or semi-spitzers excel at the ranges most game is killed — especially where quartering shots are typical. The average shot distance for the dozen deer, elk and African plains animals I’ve shot most recently: 103 yards. Seldom is an animal so far or a sneak so difficult that I can’t get close enough to aim dead-on with a semi-spitzer. In fact, I recall fewer than a dozen shots in 50 years that all but mandated a pointed bullet.

More often, I’ve been pleased there was a heavy bullet in the barrel.

Not long ago, bellying through thin grass on loose sand toward a blue wildebeest in a thorn patch, I could see only a suggestion of the bull in its bed. At about 50 yards, I stopped and snugged the sling. The bull rose side-to but moved only to thorn’s hem before quartering steeply off. A blunt 196-grain 8mm soft-nose from my iron-sighted 8×57 drove through rear ribs, paunch and vitals toward the off-shoulder. The tough animal galloped away but nosed in under a cloud of dust about 80 yards on. The bullet’s momentum and high SD made that shot lethal.

Blunt bullets are best for short shots at durable beasts, where SD trumps BC, and in tube magazines to nix primer detonation. But are they as versatile as pointed bullets? Long bullet noses (ogives) and sharp poly tips sell well because they flatten bullet arcs and reduce the rate of velocity loss for easier hits and more punch at distance—ostensibly at no cost in killing effect up close.

Actually, there is a cost. Long, slender noses limit options for making bullets upset and penetrate predictably. Jacket thickness and the cavity size of hollow points are constrained near the tip. So, too, the shape and amount of exposed lead of soft points. While clever engineers have designed pointed bullets to open at impact speeds as low as 1,600 fps and retain their integrity to drive deep, I’m told that task isn’t easy. Small bullet diameters and nose cavities make it more difficult. Federal’s Jared Kutney says the new Terminal Ascent bullet will upset at about 1,500 fps; Swift CEO Bill Hober insists the Scirocco opens at 1,440. Jeremy Millard at Hornady tells me it’s hard to make slim copper noses peel at low speeds without “shaving BC and inviting disintegration at 3,000 fps.”

Long bullets can crowd rifle actions, throats and magazines. Deep seating in the case eats powder space. Recent “long-range” cartridges like the .224 Valkyrie, 6.5 Creedmoor, 6.5 PRC and .300 PRC are short from base to shoulder to give the neck full grip on long bullet shanks without exceeding specified cartridge overall length.

Pinocchio noses threaten flight stability unless the long bullet gets a faster spin. Until recently, standard rifling twists worked for any bullet because the heaviest ones were blunt. Fast-twist rifling is most offered in .223 rifles. Early cartridges featured 55-grain spitzers. Sisk 70-grain semi-spitzer hunting bullets were about the same length. But current match bullets, as heavy as 80 grains, are much longer and beg sharper twists than the original 1:14. As lead-free bullets are longer for their weight than jacketed lead, twist rates for the LF become critical at a lighter threshold. An accurate 1960s rifle I fed solid-copper 55-grain bullets wouldn’t keep them inside a cabbage at 100 yards. Now, .223 barrels come with a twist as fast as 1:7.5. Insufficient spin can cause bullets to enter targets sideways (keyhole).

TABLE 3

| LOAD | MUZZLE | 100 YARDS | 200 YARDS | 300 YARDS | 400 YARDS | |

| Hornady 175-gr. Roundnose, BC .285 | VELOCITY (FPS) | 2,900 | 2,579 | 2,279 | 2,000 | 1,742 |

| ENERGY (FOOT-POUNDS) | 3,267 | 2,583 | 2,018 | 1,554 | 1,180 | |

| ARCS (INCHES) | 0.0 | +1.9 | 0.0 | -8.6 | -26.0 |

TABLE 4

| LOAD | MUZZLE | 100 YARDS | 200 YARDS | 300 YARDS | 400 YARDS | |

| Hornady 175-gr. Spire Point, BC .462 | VELOCITY (FPS) | 2,900 | 2,699 | 2,507 | 2,322 | 2,146 |

| ENERGY (FOOT-POUNDS) | 3,267 | 2,830 | 2,441 | 2,096 | 1,789 | |

| ARCS (INCHES) | 0.0 | +1.6 | 0.0 | -7.2 | -20.8 |

The stability of a bullet after the hit matters, too. Ivory hunters favored heavy, blunt bullets not just for their penetration but also because they stayed on course in tough going better than pointed bullets. That’s still true. Bullets with flat noses are said to drive more reliably straight than either—the reason Woodleigh and Swift solids for heavy game now feature them. Of course, soft points change shape as they penetrate. Proper spin for stability in the air isn’t always adequate in a denser medium. A 300-grain .375 bullet from 1:14 rifling is stabilized at a rate of 2,229 rotations per second through air. Entering water, it must turn 66,870 rps to maintain stability! As animal muscles, bones and organs aren’t of uniform consistency, the ideal spin rate changes as a bullet penetrates. But bullets become shorter as they expand, reducing the spin needed for stability. A pointed bullet barely stable in the air can have a tough time staying stable after impact.

In sum, bullets with long, sharp noses aren’t beneficial at ordinary shot ranges. Their niche is The Long Poke. Their lofty BCs trace shallow arcs, defy wind and maintain speed and energy well. When you needn’t kill a township away—arguably a hard sell anytime—blunt bullet noses can deliver the result you want.

Editor’s Note: This article is an excerpt of Gun Digest 2023, 77th edition.

More On Bullets & Ballistics:

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

Read the full article here

![Walther PDP Pro-X [HANDS-ON REVIEW] Walther PDP Pro-X [HANDS-ON REVIEW]](https://www.recoilweb.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Walther-PDP-Pro-X-18.jpg)

Leave a Reply