While almost all the media attention was focused on the Allied invasion of France and the Normandy beachheads in early June 1944, the U.S. V Amphibious Corps invaded the strategically important island of Saipan, on June 15th.

The Battle of Saipan was the first move in Operation Forager, the capture of the Mariana Islands. Saipan was the key to Forager, as the island provided an airbase that put most of the Japanese home islands within the operational range of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers. If Saipan could be taken, the strategic bombing of Japan could commence.

The U.S.M.C.’s 2nd and 4th divisions, along with the U.S. Army’s 27 Infantry division, were detailed to take Saipan. Waiting for the 71,000+ assault troops were more than 25,000 troops of the Japanese Imperial Army’s 43rd Infantry Division. Saipan’s limestone caves and deep ravines made the island well-suited for the defenders. And while much of the combat in tropical forests and mountains was well-known to the Marines, the Battle of Saipan was to feature the largest tank engagement of the entire Pacific War.

The Japanese had used tanks in small numbers before, but on Saipan they had assembled a force of about 100 tanks. Their plan was to unleash their armored forces on the Marines and sweep them back to their beachheads in an armor-plated cavalry charge. What followed was an incredible struggle between men and machines that will live forever in the annals of U.S.M.C. bravery and resolve.

The Marines had met Japanese tanks before, but only in very small numbers, and within the tight confines of jungle combat. Japanese tanks were lightly armored pre-war designs, and they were in no way the equal of the AFVs battling in Europe. Even so, portions of the Saipan terrain were well-suited for tank use, and Japan hoped to surprise the Marines with an overwhelming armored thrust.

The Japanese Tanks

Japanese tanks are some of the least studied armored vehicles of World War II. While it is true that Japanese tank development lagged well behind that of European and American forces, their tankers’ aggressiveness and willingness to sacrifice were second to none. Large attacks by Japanese tanks were infrequent (Battle of Saipan, Battle of Peleliu, and the Philippines campaign were the best examples), and most of their AFVs were frittered away in small attacks or used as mobile bunkers.

The Japanese developed medium tanks (armed with a high velocity 75mm gun) that would have been far more effective in tank-versus-tank fighting. Of these, only the Type 3 “Chi-Nu” was produced in any numbers, and were held in reserve on the Japanese home islands.

Type 95 Ha-Go Light Tank: Japan’s first modern battle tank, in service from 1936. The Type 95 featured a three-man crew, with a 37mm in a small (one-man) turret. Armor protection was just 12mm maximum. The Type 95 was an average light tank design, but by 1944 it was no longer competitive in tank-versus-tank combat. Sherman tank gunners often found their 75mm armor-piercing rounds passing right through the Type 95’s thin armor, and switched to high explosive rounds to blast the Japanese light tanks apart.

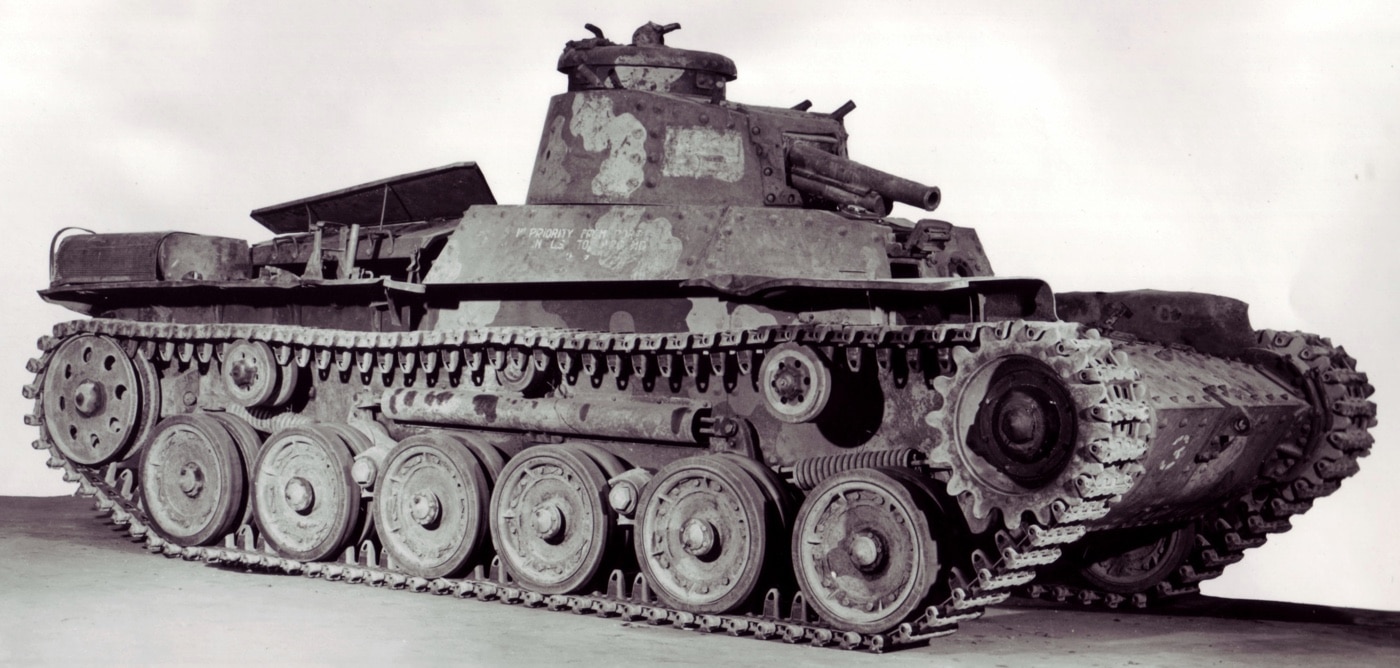

Type 97 Chi-Ha Medium Tank: The Type 97 was designed primarily for infantry support and was equipped with a low-velocity 57mm Type 97 tank gun. Armor protection was 25mm maximum. This was Japan’s most produced tank in WWII.

Type 97 Shinhoto Chi-Ha Medium Tank: The Type 97 Shinhoto (new turret) Chi-Ha featured a redesigned three-man turret mounting a high-velocity 47mm Type 1 tank gun. The Shinhoto Chi-Ha was the most potent of all Japanese tanks used in combat during WWII. A small amount of these tanks operated with the 9th Tank Regiment on Saipan. The Shinhoto Chi-Ha’s 47mm gun could penetrate the armor of the M4A2 Sherman tank, but only from the sides and rear, and then at relatively close range.

Type 2 Ka-Mi Amphibious Tank: Even though it was considered the best amphibious tank of the war, that didn’t make the Type 2 a decent combat vehicle. Armed with a 37mm Type 1 tank gun and protected by 12mm armor maximum, the Ka-Mi had little to offer in either infantry support or tank fighting.

The Kitchen Sink Meets the Bazooka

The first Japanese tank attack on Saipan came on the night of June 15th, and with it came the first use of the unique Type 2 Ka-Mi amphibious tank. The Marine officers had their men prepared for anything, and even the odd Japanese amphibious tanks could not get past them.

Major Carl W. Hoffman’s U.S.M.C. monograph “Saipan: The Beginning of the End” detailed the Leathernecks’ bemused reaction:

Lieutenant James R. Ray, leader of the 1st Platoon, Company F, had carefully briefed his unit prior to the landing on the fact that the Japanese would likely throw everything, “including the kitchen sink”, at the Marines. Ray stressed the importance of establishing a good defensive position after seizure of the 0-1 line so that an enemy thrust from Garapan could be stopped. When the peculiarly designed Japanese tanks appeared — looking rather like an overgrown piece of plumbing, PFC Nestor Sotelo of the 1st Platoon raised his head and shouted: “Pass the word to Mr. Ray that the Japs have arrived from Garapan with the kitchen sink.”

The Marines new anti-tank rocket launcher, the 2.36-inch bazookas, immediately proved their worth. Two of the Japanese tanks were destroyed at the front of Marine lines, while the third tank broke through and was finally destroyed within 75 yards of the 8th Marines command post.

General Saito’s Armored Thrust

“Destroy the enemy, during the night, at the water’s edge.” — Lieutenant General Saito, commander Japanese 43rd Division

On the night of June 16/17th, Lieutenant General Saito, commanding general of the Japanese 43d Division, ordered his troops to sweep the American invaders off the island of Saipan.

The U.S.M.C. history of the battle of Saipan describes the plan:

Saito based his plan on the reasonable premise that U.S. troops should be attacked before a firm beachhead could be established. It is apparent, however, that the beachhead was stronger on the 16th than it had been on the 15th; and the attack was already one day late for maximum effectiveness. In other words, nothing had developed, from the Japanese point of view, which would make a D-plus 1 attack more successful than one on D-Day. On the contrary, Marine positions were much better organized by 16 June, as more supporting weapons, supplies, and ammunition were ashore, and generally the Marine situation had improved.

A strong collection of tanks would provide an armored spearhead. Elements of the 3rd, 4th, 5th, and one-half of the 6th Companies of the 9th Tank Regiment were available for the attack. The 4th Company had been almost destroyed on D-Day attempting to defend the landing beaches, and only three of its 14 tanks remained operative. A total of 14 tanks from the 3rd Company, 14 from the 5th, seven from the 6th, six from headquarters, and three survivors from the 4th, brought the total to 44 committed to the attack.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, they no longer had the element of surprise, as Marine recon coupled with G-2 reports identified a large concentration of Japanese troops and tanks. Marine anti-tank units were briefed and ready. Even so, the coming battle would be a wild, confused night action that saw the Japanese penetrate dangerously close to a Marine command post.

The U.S.M.C. battle history picks up the story:

The attack began at about 0330, and the brunt struck Lieutenant Colonel Jones’ 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, (principally Company B) and to a lesser extent the 2d Battalion, 2d Marines, (principally the 1st Platoon, Company F). The tanks advanced in groups of four or five with Japanese soldiers clinging to them. Poor and ineffective tactics reflected the inadequacy of Saito’s order; some tanks cruised about in an aimless fashion, some bogged down in the swampy ground, some made an effort to break through the lines, still others stopped to let off their pugnacious passengers.

From a psychological point of view, a daylight attack would have been more frightening to the Marines. For here, in the dark (even with the supporting destroyers’ 5-inch star shells called in to light the area), it was impossible to estimate the number of tanks employed. No one had reason to suspect the presence of more than a dozen. But one dozen or three, the Marines did not budge from their foxholes.

Many of the Japanese troops of the 136th Infantry were riding on the tanks, clinging to crude frames, hastily applied before the attack. The rest were clumped in small groups among the vehicles. Marine machine guns and M1 rifles tore into these groups, while mortar shells exploded among them. The 75mm pack howitzers of the 10th Marines blasted the massed Japanese force with continuous volleys of direct fire. The 75mm howitzers fired more 800 rounds in the engagement. One battery of 105mm howitzers of the 10th Marines fired all of its available ammunition at the jumbled Japanese force.

Marine anti-tank gunners had fleeting glimpses of Japanese tanks rumbling about in the dark. Star shells and burning vehicles helped them identify targets, but there were far more enemy tanks than were ever expected.

A Madhouse of Noise, Tracers and Flashing Lights

The Marine history describes how the confused night action unfolded.

At 0345, the first wave of tanks began to enter the B Company sector. Their squeak and rattle could be distinguished above the shell fire and long bursts of machine gun fire as far back as the regimental command post. The battle evolved itself into a madhouse of noise, tracers and flashing lights. As tanks were hit and set afire, they silhouetted other tanks coming out of the flickering shadows to the front or already on top of the squads.

Many of the tanks were ‘unbuttoned’ (turrets open) the crew chief directing from the top of his open turret. Some were being led by a crew member afoot. They seemed to come in two waves, carrying foot troops on the long engine compartment or clustered around the turret, holding on to the hand rail. Some even had machine guns or grenade throwers set up on the tank. The bulk of the infantry followed what appeared to be the second wave of tanks, but as they came under the fire of B Company’s heavy machine guns, four of which were in the line of forward combat groups, the infantry tried to mount the tanks. Those following afoot were badly cut up.

The Japanese tanks appeared confused. As their guides and crew chiefs were hit by Marine rifle and machine gun fire, what little control they had was lost. They ambled about in the general direction of the beach, getting hit again and again until each one burst into flame or turned in aimless circles only to stop dead, stalled in its own ruts or the marshes of the low ground.

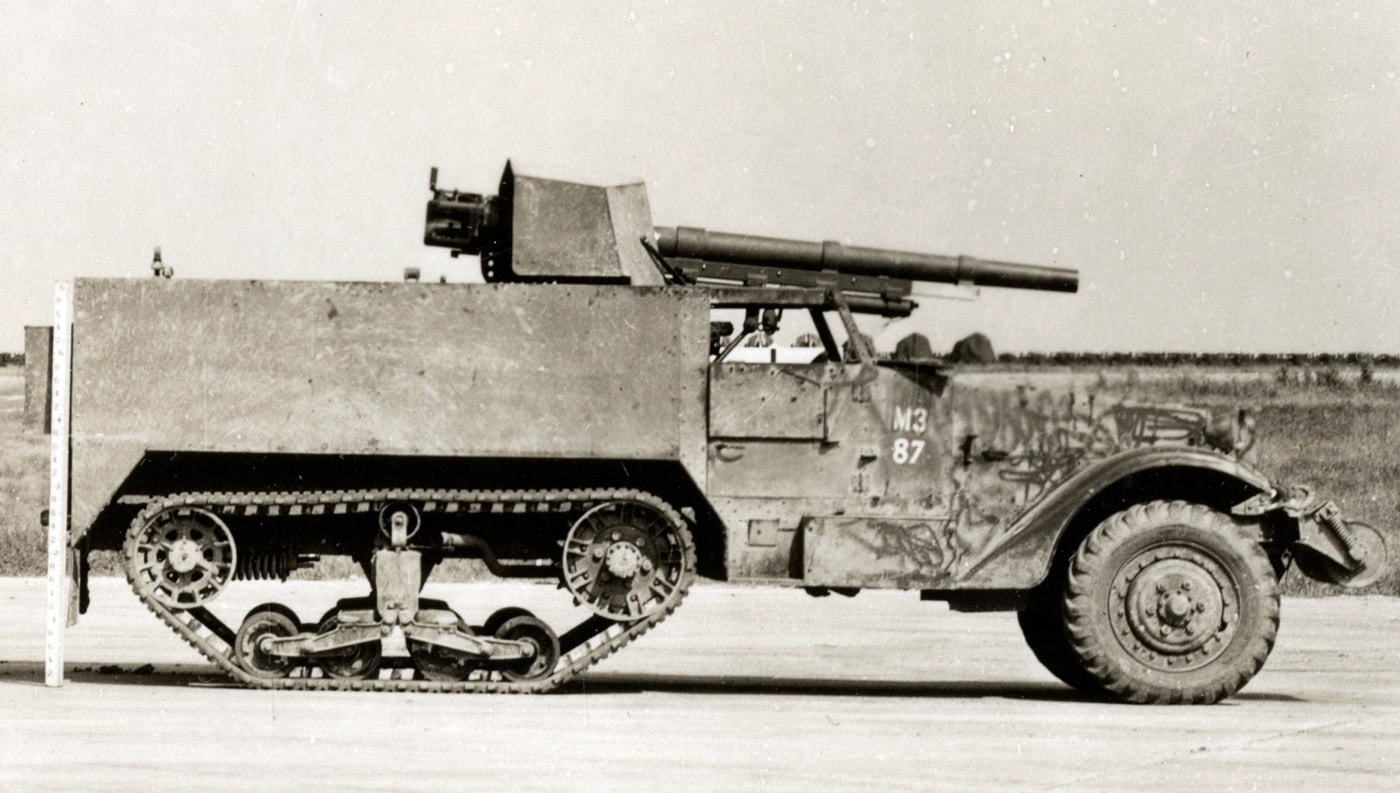

Some kept their turrets in action, doing damage until dawn when the Weapons Company’s 75mm half tracks entered the fray and quickly silenced any signs of life. Fortunately, B Company’s ‘bazooka’ teams had been put in the main line of resistance with the forward platoons for that night. These teams, with one team that came over from A Company, did outstanding work and verified the ‘bazooka’ as a superior tank buster.

The 37mm section attached to B Company had positions on each side of the road that entered the center of the company sector. In addition to the two guns, this section had one light machine gun, two bazookas, and two anti-tank grenade dischargers. The right gun jammed but the squad held its position with the bazooka and other weapons.

Several Marine Sherman tanks contributed the fire from their 75mm guns, and the Special Weapons Company’s 75mm SPM half track tank destroyers got busy with their specialty once dawn’s early light exposed plentiful targets.

Regiment had alerted the Special Weapons Company’s half tracks at the first warning and by 0415 they were underway from their position near the regimental CP. They had rough, slow going over soft ground and several lines of irrigation ditches. As dawn broke and the tanks that were not already burning were disclosed, the 75mm guns made short work of them.

The last Jap tank was spotted as it climbed the winding road to Hill 790. Its turret could be seen among a small group of buildings on top of the hill. The Naval Gunfire officer quickly adjusted and fired twenty salvos on this target. The tank sent up an oily smoke and burned the rest of the day.

Victory (but at a Cost)

There were plentiful targets that night, and despite their grievous losses, the Japanese kept up their attack. Marine machine gunners ignored the tanks and worked overtime to strip away the Japanese infantry. The Browning guns of Company F, 2nd Marines, fired more than 10,000 rounds of .30 caliber ammunition themselves. Major Warren Morris, commanding Company F, described:

I have nothing but the highest praise for the two 37mm crews. They went so far as to turn their guns around and fire, practically point blank, at tanks that broke through the lines.

The thinly armored Japanese tanks were hit multiple times by multiple weapons — so many times in fact that it was difficult to tell which weapon, bazooka, 37mm, 75mm, 105mm, or anti-tank rifle grenade, had struck the killing blow. All that really mattered to the Marines was that the Japanese tanks were stopped dead in their tracks.

The U.S.M.C. history describes:

In numerous instances the fires of many weapons converged upon a single enemy tank, and more than one Marine, from more than one unit, often claimed its destruction. Just how many were knocked out by bazookamen and how many by 37s, 75mm half-tracks and tanks cannot be accurately determined. The important thing is that the means available were adequate for the task. The Japanese effort was a dismal failure; the enemy had lost a great number of tanks — and these losses were irreplaceable. Also, the attack had convinced the Marines that they could stop a concentrated enemy tank attack with weapons organic to the infantry battalion.”

While the Japanese lost approximately 35 tanks that night, along with a large number of infantry, the stubborn Marine defenders suffered as well. The 1st Battalion, 6th Marines suffered 78 casualties, while Company F of the 2nd Marines had 19. At the end of long, difficult night, the final result was quite telling. Japan pitted their armor against U.S.M.C. flesh and bone and determination, and came up far short of their goal. By July 9th, Saipan was in American hands.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here

![Walther PDP Pro-X [HANDS-ON REVIEW] Walther PDP Pro-X [HANDS-ON REVIEW]](https://www.recoilweb.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Walther-PDP-Pro-X-18.jpg)

Leave a Reply