Being a Boomer, I grew up at a time when damn near every able-bodied dad in the neighborhood had served in World War II, and a lot of the younger ones had just come back from the Korean conflict. Souvenirs abounded. Japanese flags, German helmets, assorted edged weapons … and guns, guns, guns.

It turns out that it wasn’t just our side that appreciated those souvenirs, either. In 1984, Pantheon Books published “The Good War: An Oral History of World War Two” by Studs Terkel, based on interviews with soldiers, Marines, sailors, and airmen who had taken part in the conflict.

One soldier he debriefed was Richard “Red” Prendergast, whose unit had been hopelessly surrounded by a vastly larger force of German soldiers and panzers in the Ardennes. He told Terkel, “…the flag of truce came, and a German officer came up. They were wearing white suits. These were the elite, the crack troops of the German army.

He said to us in perfect English, to our colonel, ‘You’ve been up here for quite a while, and you haven’t fired a shot since noon. We strongly suspect you don’t have ammunition. If you don’t come down in 20 minutes, none of you are coming down.’ Our officer in charge gave that a thought for about three minutes (laughs) and he said, ‘All right, everybody, destroy your weapons.’ All I had was this beautiful .45 that I’d been treasuring. I took it all apart and threw it in the snow.”

Prendergast went on, “They were furious that we’d destroyed our weapons. Actually, their P-38s and Lugers were superior pistols, but they liked .45s for souvenirs.”

Whaddaya know? The other side did the same thing. And while I respectfully disagree that the Walther P-38 and the Luger were better than the American 1911, that’s a topic for another time.

Why were the enemy’s weapons, particularly his handguns, so treasured as souvenirs? A part of it was undoubtedly psychological. Like defanging a venomous snake, taking an enemy’s weapon is symbolic of having defeated him in combat with life on the line, a solemn reminder of the stakes and the price of victory.

However, it was also a practical thing. A handgun was a most useful thing to possess in combat. During the up close and personal trench warfare of World War I, the American Supreme Commander General John Pershing had wanted every American doughboy to have a .45 caliber sidearm as well as a bolt action service rifle, and supposedly this is one reason Model 1917 service revolvers were produced to supplement the limited supply of 1911 .45 autos.

Some Brought Their Own

It was not unknown for Americans to bring their own handguns to war with them. Any student of the gun knows that General George Patton brought several of his own firearms to the front. On one occasion, Patton purportedly emptied his .380 pistol at a German plane that was strafing his camp, and on another, he used his trademark ivory-handled .357 Magnum to shoot a mule that was blocking a bridge.

FBI agent Walter Walsh, serving with the Marines in the Pacific, used his personal 1911 .45 auto to kill a Japanese sniper at a range of 90 yards. My older daughter owns a .38 Special revolver that a Navy cook brought with him to the Pacific theater and used to kill two Japanese sappers who had invaded a Marine camp. The legendary U.S.M.C. Lt. Col. Jeff Cooper killed his first enemy soldier on a Pacific island with a .45 caliber Colt Single Action Army revolver he’d brought with him from home.

Sometimes, American warfighters had their families send them handguns. The late gun writer Dean Grennell was an aerial gunnery instructor in World War II. He told of a Korean War vet whose loved ones shipped a .44 Special revolver to him at the front, along with a box of ammo, concealed inside a canned ham to skirt regulations. During the Vietnam conflict, many did the same.

Yanks scrounged handguns wherever they could. World War II Marine combat vet James Jones captured the mentality of it in his fact-based novel “The Pistol.” Jones’ prose captured the confidence that a purloined 1911 .45 gave to a young American fighting man…and to others like him, who coveted his pistol.

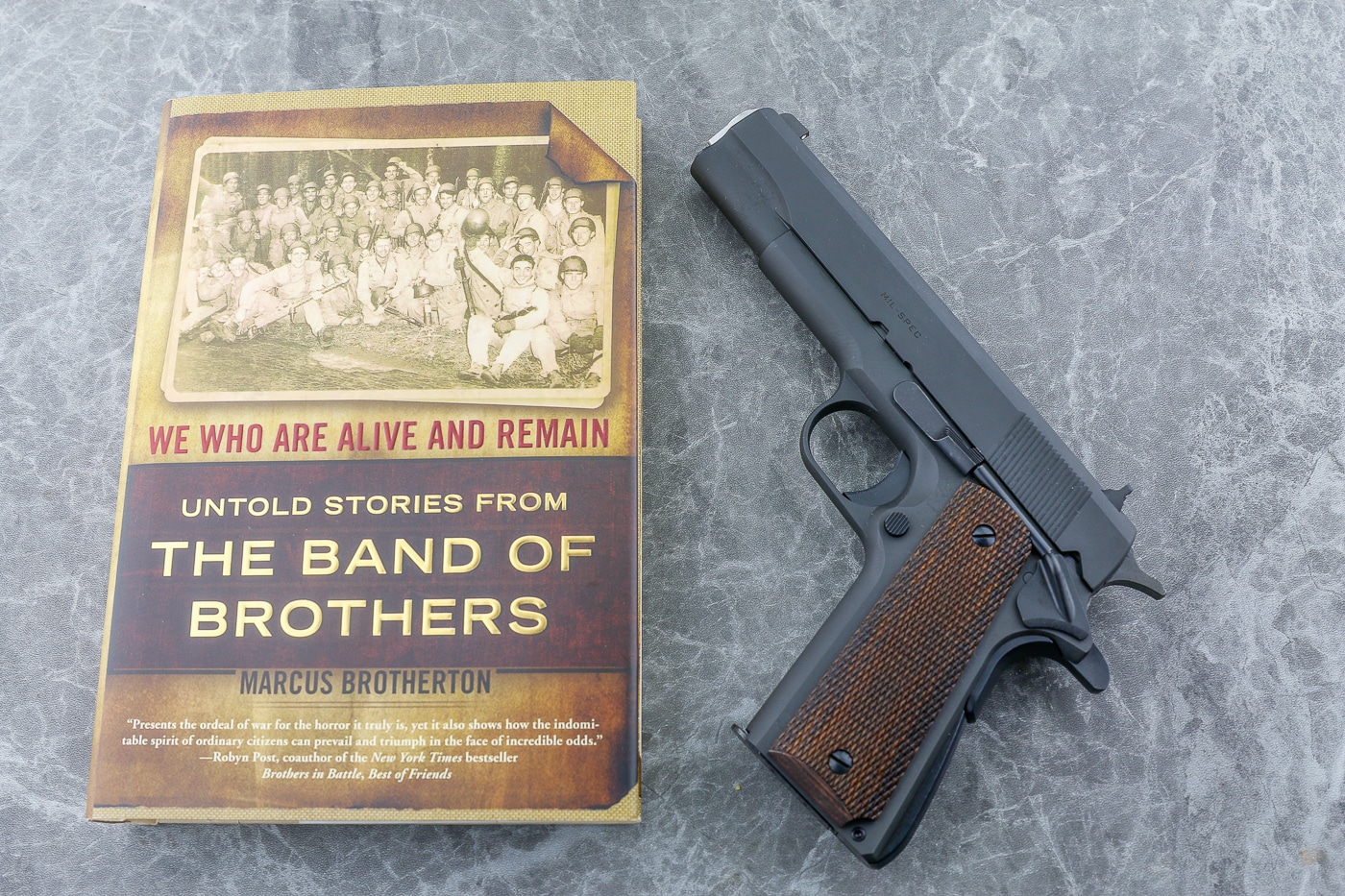

If a soldier couldn’t get an American .45, a German 9mm would do. In the non-fiction book “Band of Brothers” by Stephen Ambrose and the HBO TV series based on it, we meet Cpl. Donald Hoobler, who landed on D-Day and spent a long time seeking his grail souvenir, a Luger. He finally got one, taken from a German he killed. He carried it loaded as a backup until, tragically, it went off in his pants, piercing his femoral artery and killing him.

Many of the take-home guns were Uncle Sam’s own, seen by many as fair compensation for risking one’s life for his country. Harry Truman, 33rd President of the United States, came back from World War I with no fewer than three G.I.-issue .45s: a 1911, and two 1917 revolvers. Those guns reside today in the Truman Library in Missouri.

Interestingly, the vast majority of bring-back enemy handguns were German: the P-38, the Luger, and a significant number of PP and PPK pistols favored by German officers. It was highly unusual to find a vet from the Pacific theater who had brought back a Nambu handgun. They were known even then to be absolute junk. The favored souvenir from the Pacific seems to have been the Japanese sword.

Meanwhile, Stateside…

The psychology of the enemy’s weapon being a trophy extended to the “War on Crime” stateside. Legendary Texas Ranger Frank Hamer, who led the posse that killed the notorious Bonnie and Clyde, was stiffed by the Texas governor who’d hired him but got to keep, and sell, the many guns that were found in the deadly couple’s shot-up Ford V-8 sedan.

Another famous Ranger, Manuel “Lone Wolf” Gonzaulles, claimed that at the end of his 30-year career he had amassed a collection of 580 firearms. Many of them were customized personal weapons, but many were souvenirs taken from criminals he had either arrested or killed in the line of duty.

The practice of officers keeping guns they confiscated from criminals has faded, but is still occasionally seen in the 21st century. I learned a lot debriefing Ukiah, California, police officer Marcus Young, who on March 7 of 2003 was ambushed by a vicious psycho who shot him five times with a snub-nose .38 Special. Though wounded in both arms, Marcus was able to return fire and kill his assailant. In addition to various citations for heroism, he was awarded the gun he had been shot with, and for a while carried that little revolver as a backup.

Tradition

Keeping the claws of the creature that wanted to kill you seems to be a natural human inclination after surviving life-threatening combat. Many of those souvenir guns are still in private hands, often inherited from forbears who fought for American freedom.

They aren’t just souvenirs. They’re symbols.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply