Most of us — from the tool tyro to the edged aficionado — know when a knife is dull. There’s trouble in paradise when it takes tremendous effort to break down a cardboard box, when a blade fails to catch a fingernail, and when what should be a clean slice across paper instead results in a ragged tear. For the longest time, however, I had little idea what to do when these issues reared their ugly heads. My solution was to simply to throw money at the problem: I’d buy a new pocket knife each year.

As I got a little older and wiser, I realized that I didn’t need to put my old favorites out to pasture, though restoring an edge was easier said than done. Through trial-and-error and a lot of research, I would learn there’s a lot of roads to getting a blade back to “sharp.” Let me explain what I’ve learned in the last twenty years when it comes to sharpening, honing, and stropping — three very different approaches that may be more or less useful depending on your knife and what it needs.

Sharpening

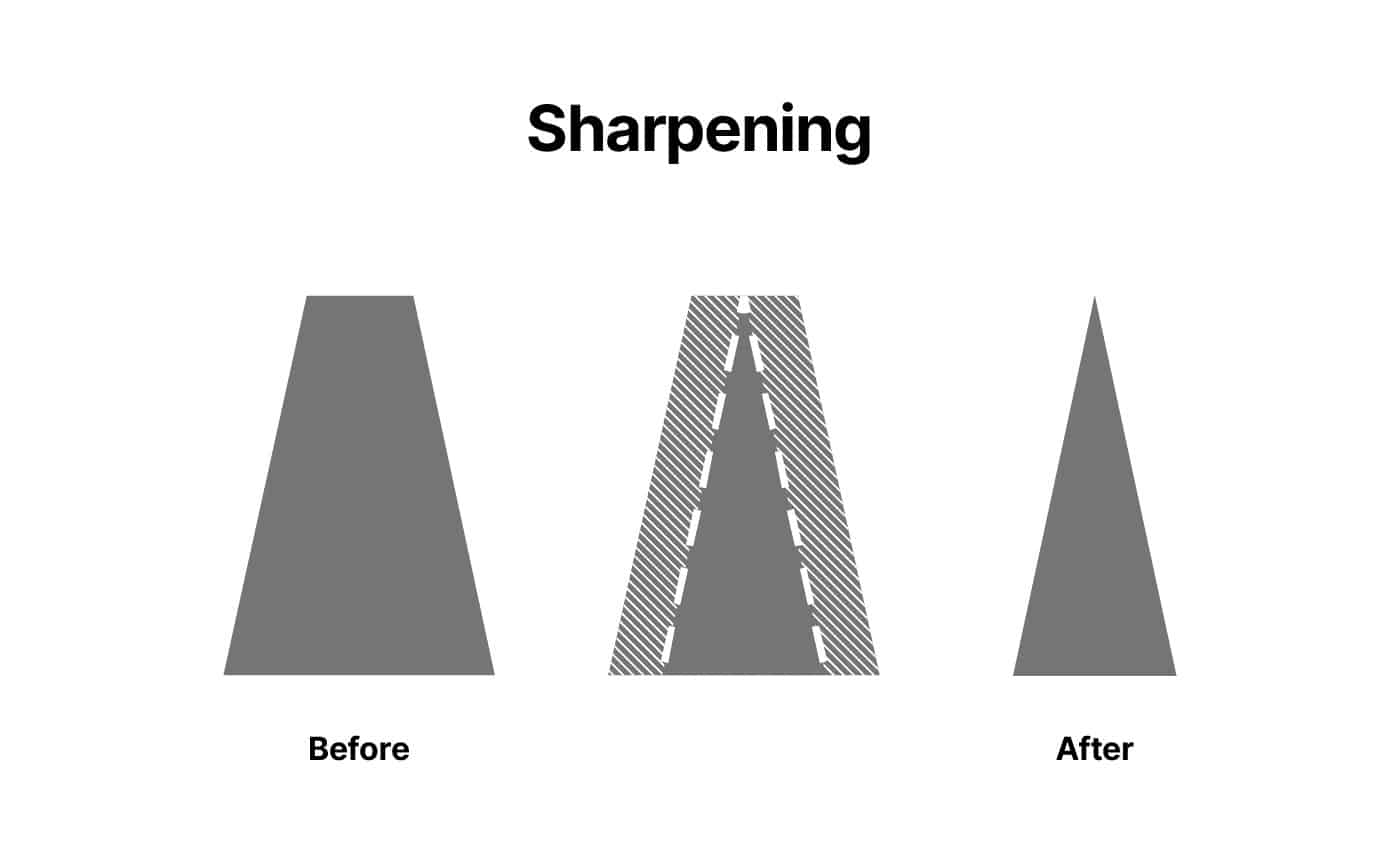

Semantically, most people hear this word and associate it with anything that makes the knife sharper. However, to those in the knife world, sharpening refers specifically to the process of removing metal in order to change the geometry of the blade’s edge.

With many dull knives, the issue is that the cutting edge has worn away and flattened out under sustained use. If viewed via cross-section, the edge resembles less of a triangle and more of a trapezoid. Since metal can’t be added where we want it — at least not to a degree that would be practical or cost-effective — the sides need to be worn away so that the correct geometry is reestablished.

Sharpening tools typically include whetstones or pull-through sharpeners (yuck: a story for another day) that rely on abrasive materials to rapidly and aggressively wear at the exposed metal of a cutting edge. Like sandpaper, sharpeners are measured in “grit.” Perhaps counter-intuitively, low-grit sharpeners are roughest, and used first to remove the most material with the least amount of elbow grease. From there, high-grit sharpeners are used to refine the blade. Extremely high-grit compounds can produce a mirror-polished edge.

Theoretically, a knife can always be sharpened to restore a functional edge. However, it might not be the case that you actually need to remove much (or any) steel to produce a keen edge.

[Catch Randall Chaney’s article How to Sharpen a Knife for more information.]

Honing

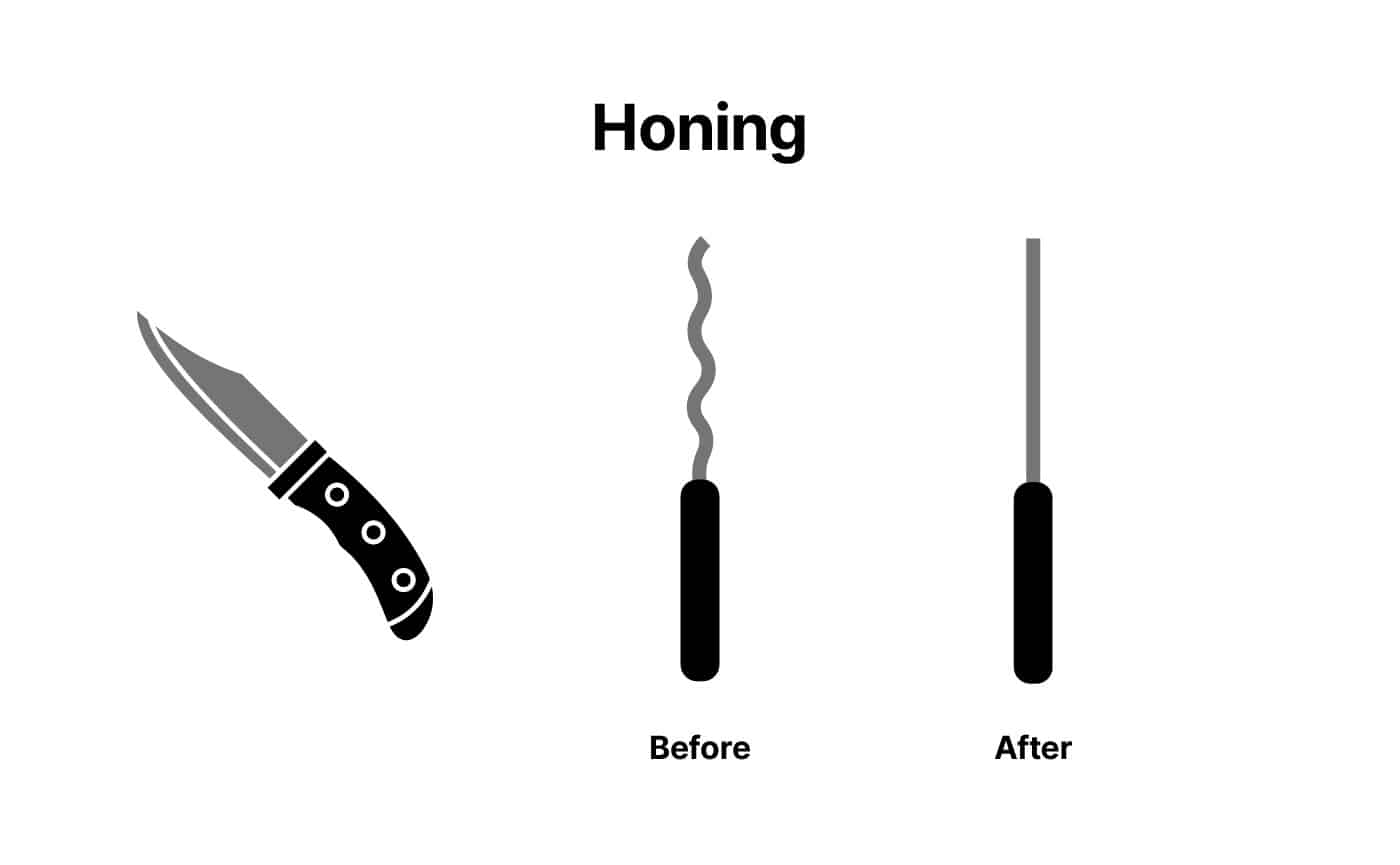

If your knife won’t cut, it may be possible that the edge is simply misaligned. As a knife is used, certain parts of the blade might be moved out of position or bent ever so slightly. Ideally, the cutting edge of any knife should look like a straight line when viewed dead on. However, under use — and especially as the edge comes into contact with hard compounds — it may end up looking more like a wave or squiggle. This phenomenon is especially common among knives made out of softer steel compounds.

Honing is the process of pushing the blade edge back into proper alignment. Most typically, it’s done with a cylindrical length of honing steel. (If you’ve ever wondered what that rod in your knife block was for, now you know.)

Likely you’ve seen footage of chefs like Gordon Ramsay rapidly flashing the knife against steel in a free-hand fashion as it makes a “snick-snick-snick” noise. If it isn’t simply theatrics we’re witnessing, I’d wager it takes years of practice before you get good enough to hone anything that way.

The method I find works best is to hold the honing rod in place perpendicular to a potholder or PVC cutting board. With the steel held stationary, find the angle of your knife and run it downward against the rod, working from the rear of the blade to the tip in a smooth, even stroke. Then, do the same on the alternate side of the blade. Repeat that process about 10 to 20 times. Surprisingly, you don’t need to be all that precise to obtain satisfactory results.

A note here. Once you become familiar with a honing steel, your heart may warm to a lot of soft steels. Most kitchen knives are intentionally made from softer stainless steel compounds so that the edge can be rapidly brought back through some quick honing. And, because they have typically thin edges, they’re more apt to deform if they hit something like a bone or the hard wood of a cutting board. I’ve also found that many EDC knife steels, including 8CrMoV13, AUS8, and AUS10 are very amenable to honing, as are the “el cheapo” 3Cr, 5Cr, and 7Cr families. (As well as any “gas station” quality knife, whose mystery steel is bound to be soft.)

Stropping

If you’ve seen a barber running a straight razor across a strip of leather, you’ve witnessed stropping firsthand.

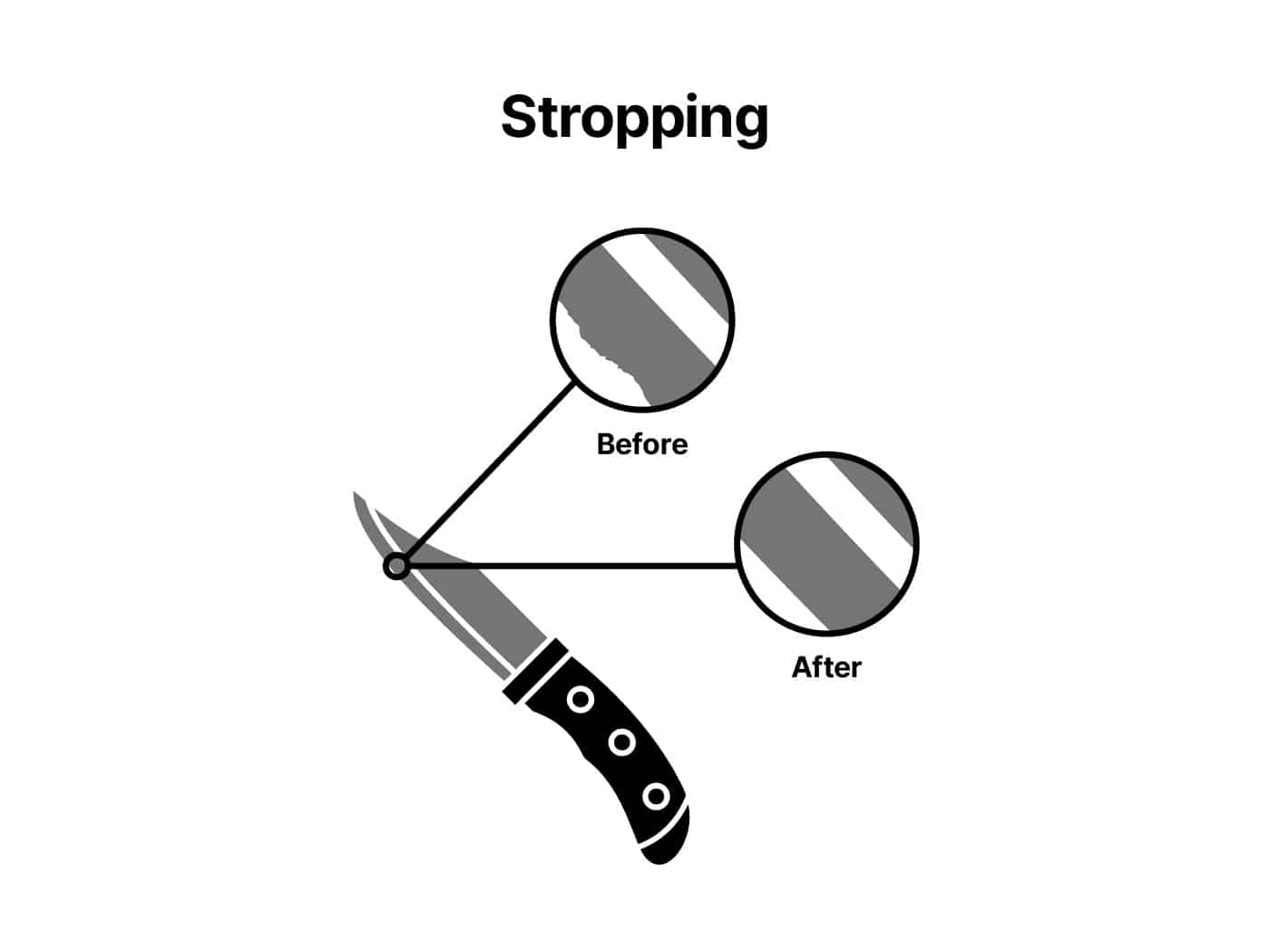

Stropping makes a sharp blade even sharper. Just about any quality knife purchased from a reputable manufacturer will have an edge keen enough to cleanly slice through a sheet of printer paper. However, if you try to use that same knife to (carefully) shave the hair from your forearm, you’ll quickly observe that not all edges are up to the task.

Stropping is a “last mile” technique that gets a blade hair-poppingly sharp. Essentially, the process of rubbing the knife edge across the strop surface polishes away rough bumps and imperfections. Like sharpening, stropping is removing metal, but it’s doing it at a much slower rate and not with any intent to change the geometry of the existing edge. Visually, you may not be able to detect a difference in the way the blade looks before stropping and afterward. If done right, however, you will notice a difference in cutting performance.

In olden days, people used cow or camel leather alone. I’ve heard it argued that these hides have some trace amount of hard silcates that makes them suited for the task. Others have asserted silicates attach themselves to the strop through the absorption of chemicals used in the tanning process. Whatever the mechanism for why cowhide alone works, most of us agree that applying a compound prior to stropping makes the technique vastly more effective.

The Knafs stropping compound on my desk, for example, lists that it’s made from chromium oxide, aluminum oxide, and stearic acid at 6000 grit. That’s very fine: about an order of magnitude finer than the least abrasive grit you’ll find packaged with most consumer-grade sharpeners. The stuff comes in a solid block, which you use almost like a stick of chalk to work into the pores of your strop.

When stropping, it’s easiest to lay the material flat on the table in front of you. With the edge of the knife parallel to the strop, you want to push and gradually rotate the blade edge into the leather until it just begins to “bite.” That’s your blade angle. With that angle established, pull the knife backwards across the strop about six or seven times, and then repeat on the other side.

Again, stropping is a poor technique to employ on dull or barely sharp edges. It’s not to say you can’t strop a dull knife into sharpness, but it’s an activity that may take all day if it works at all. Instead, it’s best to verify you’ve got a functional, “work sharp” edge capable of cutting most materials before you try to further refine it.

Sharp Mind, Sharp Blade

Simply knowing these three different use cases will probably lead you to an approach that restores your edge in the least amount of time. Are you doubtful the knife was ever a good cutter? Probably sharpening is the way to go. Is your knife made from a soft steel you remember being sharp some time ago? Honing might be in order. Do you have an already-sharp knife you want to get sharper? Apply some compound to your strop and get to work.

Again, context will determine what approach is best. But, with the knowledge of the techniques above and a little curiosity, even the layperson can maintain just about any knife in their EDC gear, kitchen drawer, or survival kit. Life’s too short to deal with a dull knife!

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply