The Douglas X-3 Stiletto was an experimental aircraft designed to test sustained Mach 2 flight, using titanium structures in aircraft construction as well as an aircraft design with an extremely short wingspan. The X-3 was one of the “X” series of aircraft designed during the early days of jet-powered aircraft.

Previous X aircraft included the rocket-powered X-1 piloted by USAF Captain Chuck Yeager, which was air-launched at 23,000 feet from the bomb bay of a Boeing B-29 and then used its engine to climb to its test altitude. It was the first aircraft to break the sound barrier, reaching a speed of 700 miles per hour at 43,000 feet.

The Bell X-2 was a rocket-powered, swept-wing research aircraft, also air-launched, that was designed to investigate the structural effects of stability and control effectiveness at high speeds and altitudes, as well as aerodynamic heating. The joint program was developed jointly by Bell Aircraft, the U.S.A.F., and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) to explore supersonic flight and to surpass the speed and altitude records of the X-1 series aircraft.

X-3 Design

In June 1949, the Douglas Aircraft Company was approved to construct two X-3 test aircraft. Douglas engineers wanted an aircraft with a maximum speed of 2,000 mph. Another requirement was that it could take off under its own power, as previous designs were carried to altitude and dropped by larger aircraft.

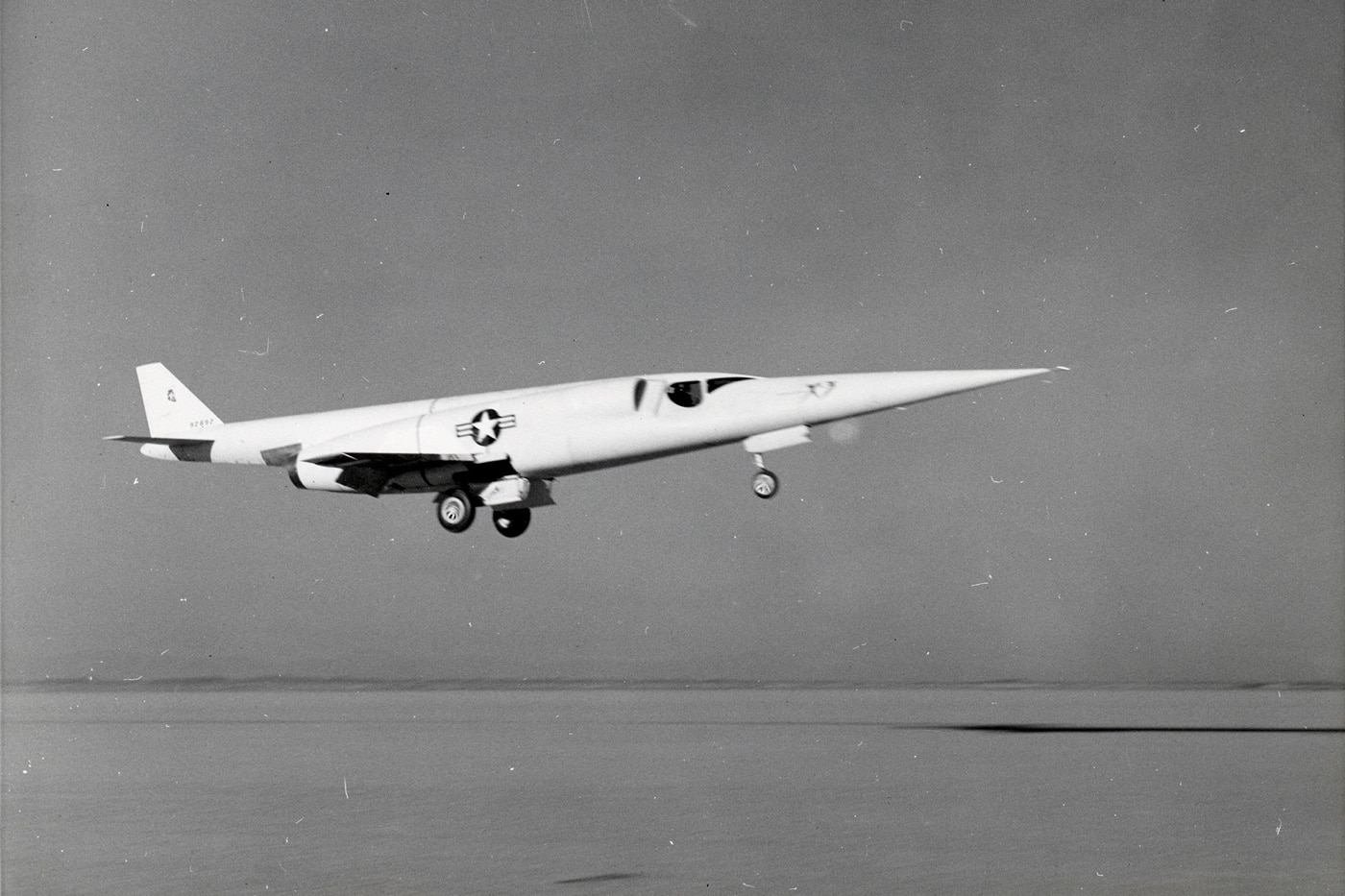

They created an extremely slender design with a long, tapered nose for mounting test equipment inside, and low aspect ratio wings. The aircraft has a semi-buried cockpit and windshield designed to combat the effects of “Thermal Thicket,” which is the effect of aerodynamic heating on the temperature of the aircraft skin and heat transfer into the structure, the cockpit, the equipment bays, and the electrical, hydraulic and fuel systems. Engineers have to incorporate countermeasures for thermal thicket in supersonic aircraft design.

Although Douglas was authorized to build two aircraft, the second was only partially constructed and then cannibalized for spare parts.

Underpowered Stiletto

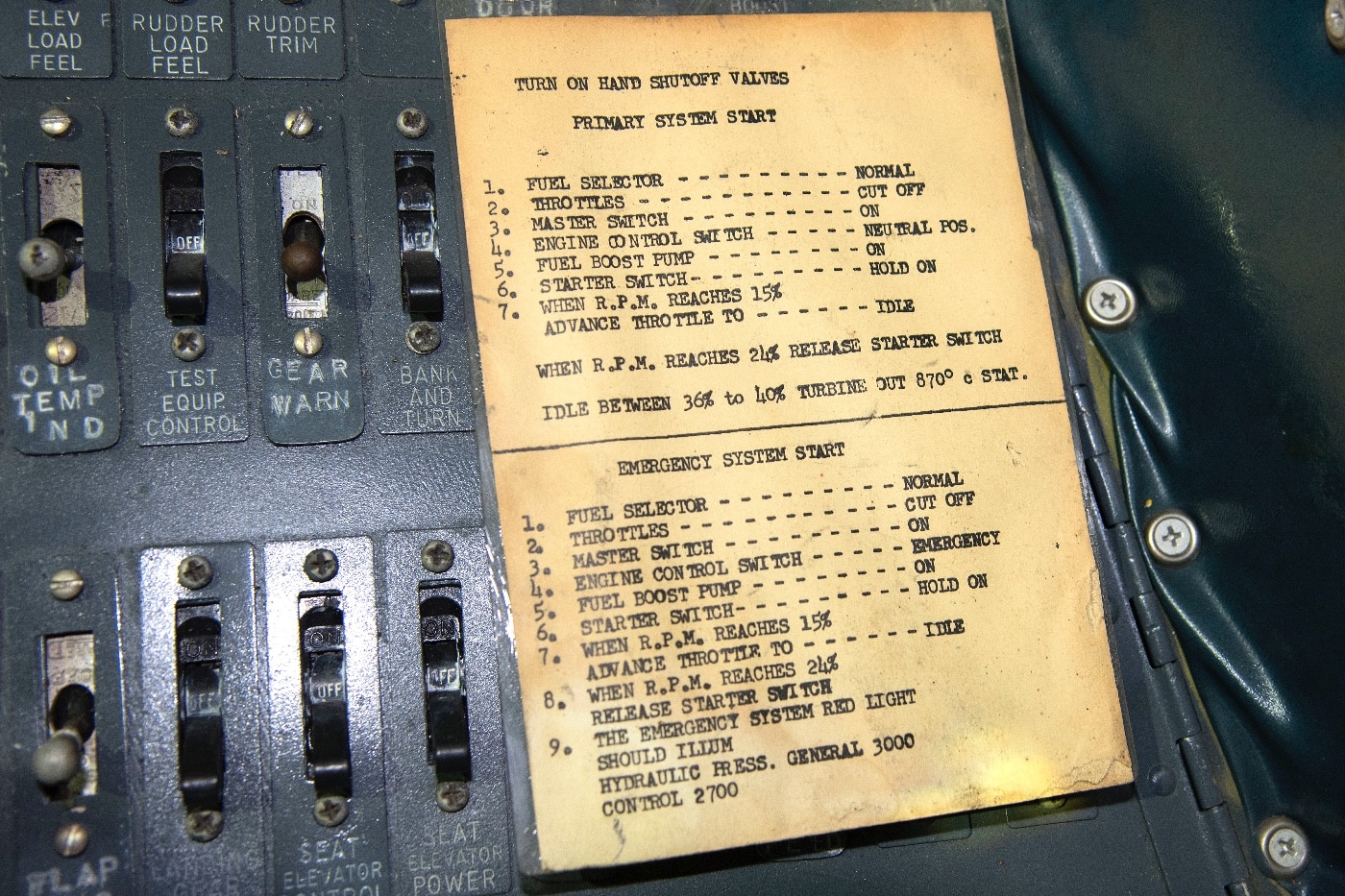

The original design called for Westinghouse J46 engines with a planned thrust of 7,000 pounds, but design difficulties forced the X-3 team to use Westinghouse J34 engines, which produced 4,900 pounds of thrust while in afterburner.

The engine issue severely limited the X-3 program, and the aircraft could only achieve Mach 1 speed when put into a dive. The fastest speed achieved in the X-3 was Mach 1.208 while in a 30-degree dive.

The “Hop”

The X-3 made its first test flight at Edwards AFB, Calif., in October 1952. Douglas test pilot Bill Bridgeman performed a high-speed taxi test, and the X-3 lifted off the ground for a distance of one mile. The “official” first flight came a few days later when Bridgeman flew the aircraft for about 20 minutes.

By the end of the Douglas test flights in December 1953, Bridgeman had made 26 flights and the verdict was that the X-3 was severely underpowered, making it difficult to control.

On to the Air Force

Now that the contractor testing phase was over, the X-3 was turned over to the USAF. Major Chuck Yeager and Lt. Col. Frank Everest each made three test flights to gain experience with low-aspect winged aircraft.

In July 1954, the X-3 was turned over to NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics) to test stability, control wing and tail loads, and pressure distribution across the aircraft surfaces.

Roll Inertia Coupling

On October 27, 1954, the X-3 experienced its most significant flight when it encountered “roll inertia coupling.” This occurs when a maneuver in one axis causes an uncommanded maneuver in one or two others.

NACA test pilot Joseph A Walker was at the controls conducting stability testing. Walker rolled the aircraft while flying at Mach 0.92 at 30,000 feet. The aircraft rolled, pitched 20 degrees, and yawed 16 degrees, which caused the aircraft to start gyrating. Walker was able to bring the X-3 back under control after about five seconds.

Walker then performed the next test. He started a dive and, when the aircraft reached Mach 1.154, he again rolled the aircraft. X-3 pitched down and measured a G-force of -6.7 Gs, then pitched up to +7 Gs, and then side slipped at 2 Gs. Walker got the aircraft under control and returned to base.

Upon inspection, it was determined the X-3 had been stressed to its limit. The plane was grounded for almost a year while engineers researched this phenomenon. It was discovered that North American Aviation experienced a similar problem with its F-100 Super Sabre test aircraft.

When testing resumed, the program never explored roll stability and control limits again. Walker made another ten test flights without mishap. Unfortunately, Walker would later be killed on June 8, 1966, during flight tests of the XB-70 Valkyrie bomber when his F-104 Starfighter was pulled into the Valkyrie’s engine wake, rolling over the top of the bomber, which disabled the aircraft. His Starfighter exploded, with both aircraft crashing onto the desert floor near Barstow, California.

The Legacy

The Stiletto was arguably one of the sleekest, coolest aircraft built, at least, I thought so, because I had a Stiletto model hanging from my bedroom ceiling as a boy.

Although the X-3 did not deliver the intended results, its short service provided data in several areas critical to modern jet aircraft design. The high speeds required for takeoff (260 mph) and landing caused changes in aircraft tire design.

The roll inertia coupling incident provided data to understand and prevent future incidents, its titanium construction provided machining techniques used on the SR-71 and X-15, and its short stubby low-aspect-ratio wing was used in the F-104 Starfighter.

In 1956, after 51 test flights, the X-3 was transferred to the National Museum of the United States Air Force, where it is now displayed in the research and development aircraft section.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Read the full article here

![SIG Sauer P365 XMACRO COMP: Skinny Compact CCW [Hands-On Review] SIG Sauer P365 XMACRO COMP: Skinny Compact CCW [Hands-On Review]](https://www.recoilweb.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/XMACRO-1.jpg)

Leave a Reply