Most people labor under the misconception that, in the battle between a firearm and a knife, the gun always wins. While under most circumstances this is true, it’s not always so—and thinking it is can be detrimental to survival. What are the do’s and don’ts of bringing a gun to a knife fight?

As with all personal combat, it boils down to relying on a dependable set of skills specific to solving the tactical problem. In personal defense against one or more assailants wielding edged weapons at conversational ranges, is your everyday concealed-carry handgun and current training level an optimal solution? What are the five best recommended practices for employing ballistic use of force against deadly edged weapons?

Before delving into the top five recommended best practices, let’s first dispel the five most common myths about relying on a firearm in self-defense against a violent physical altercation with a knife.

Myth 1: A gun is superior to a knife

The one and only time a gun is superior to a knife is when there is sufficient time and distance between combatants. Not all reaction time is created equal. For example, if you are carrying concealed and you turn a corner where some thug pulls a blade on you at bad-breath range (less than an arm’s length away), your gun is suddenly transformed into a paperweight because it is inaccessible in a timely manner.

Your attention must then transfer to the more immediate problem—avoid getting flayed open. You are not afforded the time it takes to access, deploy and align the muzzle of your concealed firearm against a lethal threat. In these situations, the knife, given such a compressed amount of time and distance (reactionary gap), is superior to the gun. A compressed reactionary gap favors the knife, whereas an expanded reactionary gap favors the firearm.

Myth 2: If an assailant has a knife, I’ll just shoot them

If you’re about 20 yards away from an attacker armed with a knife, and if you’re mentally switched on (applying good situational awareness), and if you happen to observe the attacker moving toward you screaming “I’m gonna kill you,” and if you have the requisite training, and if you have the subconscious reaction time, and if you have the commensurate shooting-performance level, and if you do everything right (make no mistakes such as glitching the draw, bad grip, trigger freeze, misalignment, etc.), and if you are justified, and if you have a good backstop, and if there are no “no-shoots” in the vicinity and if you make effective combat round placement, then yes, you may be successful in utilization of your firearm in self-defense.

However, do the math—that’s about a dozen “ifs.” If it’s your lucky day and the planets happen to align properly, then the odds are that you may be able to rely solely on that defensive option. Change one variable, one factor or introduce a single failure point and it changes the entire complexion of the shooting solution. If you fail to possess the requisite training and skill to solve this specific technical problem, then you’re more likely to rely on Lady Luck and her stepsister, Hope.

Since distance is your friend when you’re facing an edged weapon, another tool in your arsenal is the ability to create distance—think of it as defensive cardio.

Myth 3: I use the 21-foot Rule

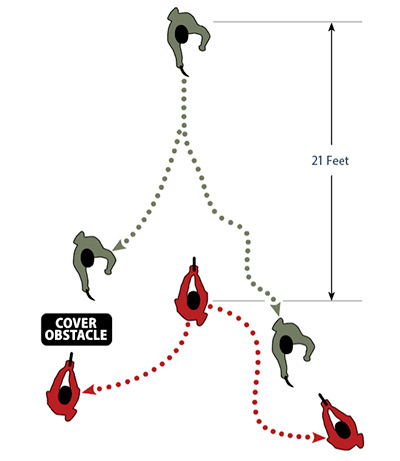

The so-called “21-foot rule” originated from research conducted by Dennis Tueller, a Salt Lake City police officer and firearms instructor, in the early 1980s. Tueller sought to determine how quickly an assailant armed with a knife could close the distance to an officer with a holstered firearm.

Through timed drills, he found that an average person could cover 21 feet (about 6.4 meters) in 1.5 seconds, roughly the same time it took for an officer to recognize the threat, draw their sidearm and fire a single defensive shot.

Tueller’s findings were published in a 1983 police training article titled “How Close is Too Close?” leading to what became informally known as the “Tueller Drill” or the “21-foot rule.” Over time, it influenced police training, reinforcing the idea that an attacker within this range posed an imminent threat, even before making contact. However, it was never intended as a strict rule, but rather a guideline to stress the importance of reaction time, movement and defensive tactics against close-quarters threats.

The “21-foot rule” is neither a rule nor a law. It is nothing more than a defensive principle applicable to self-defense that suggests an attacker armed with a knife within 21 feet poses an immediate threat, even against a drawn firearm.

More recent studies by various federal agencies demonstrate that a male assailant between the ages of 16 and 32 can close the distance of 30 feet (10 yards) in less than 2 seconds, often faster than an individual can recognize the threat, draw and accurately fire a pistol. This emphasizes the importance of situational awareness, movement and defensive tactics beyond simply relying upon a firearm. The “21-foot” principle merely highlights the dangers of close-quarter engagements and the need for effective training in response to edged-weapon attacks.

Myth 4: He shouldn’t have brought a knife to a gunfight

Probably the most prolific of all the myths about employing a firearm in self-defense in a violent physical altercation involving an edged weapon, this is one that most shooters struggle with because of mindset. Most shooters believe that an altercation with an edged weapon is a gunfight. Technically, and in practical application, this is a misnomer.

You would not have drawn your gun in a lawful manner if there were no clear and present danger presenting itself in such a way that you felt that your life or limb, or that of a loved one, was threatened with lethal use of force by way of an edged-weapon attack.

The firearm is a reactionary defensive option. It is deployed in response to a lethal threat. Whether or not immediately observed, an attack commences the moment a knife is produced and applied in a threatening manner by one or more assailants. The attack itself is what initiates the action/reaction power curve. Since action always precedes reaction, you are automatically placed behind the curve and are tasked with catching up and eventually moving to the front of the curve.

The edged weapon is produced first in an attack—which is more accurately described as an edged-weapon attack—not a gunfight. You are behind the curve and your gun, even if you are capable of an on-demand, repeatable sub-second draw from concealment, is always the last weapon to be presented.

Myth 5: Once I hit him (make round placement) it’s game over

The easiest of all myths to bust is this one. Get set up with Simunitions gear or even an Airsoft replica. Run a simple training drill: use a military-age runner (equipped with protective gear) either 21 or 30 feet from the shooter with a training knife pointing at the shooter.

The shooter starts with the firearm-training replica holstered, and on the “go” command, the runner (again, wearing appropriate protective equipment) moves at maximum attack speed toward the shooter (again utilizing either Simunitions, Airsoft or equivalent). The objective is for the shooter to draw, present and align the pistol, then fire as many rounds at the assailant(s) as possible prior to physical contact with the training knife.

You will find that you may get one, two or maybe even three rounds off (if you’re skilled enough) prior to contact. Observe where those rounds landed. The best thing is to record it and review the video later.

Having run this exact drill multiple times myself and with various agencies over the past three decades, you will find that there is, if any, minimal effective-round placement. Even if your skill level is so solid that you can consistently land two to three rounds in the upper thoracic, the assailant—unlike actors who fall “dead” to a single shot in movies—can live through it and will continue their attack for at least another minute or so. There is plenty of case history supporting this finding. The fight is not over until the threat is definitively stopped.

Having allayed the five most common myths of using a firearm against a knife attack, what then are the top five best recommended practices?

If you are attacked by an assailant armed with a knife (or impact weapon), movement away from the attacker—and any obstacles you can place between you and him—can buy precious seconds with which to react.

Situational awareness is your ability to perceive, understand, and anticipate potential threats in your environment before they become immediate dangers. It involves actively scanning surroundings, recognizing suspicious behavior and assessing potential escape routes or defensive options in real time. Rather than just passively observing, it requires a proactive mindset, keeping you alert to possible threats (mentally connected to your environment) while avoiding unnecessary paranoia.

For a defense-minded citizen, situational awareness serves as your first layer of self-defense—helping to avoid, de-escalate or prepare for a confrontation before it escalates into violence. Attackers often seek easy, unaware targets. Individuals who display confidence, alertness and readiness are less likely to be chosen as victims. It also allows for faster reaction times, which can mean the difference between escape, deterrence or being forced into a deadly force situation.

The Cooper Color Code, developed by Col. Jeff Cooper, is often used to explain levels of situational awareness. The stages range from Condition White (unaware, unprepared) to Condition Yellow (relaxed awareness, best for daily life), Condition Orange (specific alert, potential threat detected) and Condition Red (immediate action required). Proper situational awareness helps to prevent ambushes, recognize pre-attack indicators and make

tactical decisions early, such as moving to a safer position, preparing a defensive tool or escaping before violence occurs.

In self-defense, the best fight is the one you avoid, and situational awareness maximizes the ability to do just that. However, if conflict is unavoidable, being alert and ready gives you the priceless seconds needed to respond effectively, whether that means drawing a weapon, seeking cover or engaging in countermeasures. Good situational awareness is what keeps you ahead of the action/reaction power curve.

Creating and maintaining distance is a fundamental principle in self-defense, especially in a knife attack. Utilizing a firearm effectively in such a situation is greatly dependent on having an expanded reactionary gap, as it increases both time and options for response. Without adequate space, reaction time is diminished, placing you at greater risk.

Control in any confrontation begins with mastering the elements that dictate an engagement, much like operating a vehicle where steering, braking and acceleration must be managed. In self-defense, these elements are time and space. When challenged with an edged-weapon attack in close quarters, where gaining distance is not an option, changing your physical position is your best option. Instead of standing directly in front of the attack, it is imperative to move off the line of attack, meaning shift laterally or angle yourself away from the direct path of the weapon.

The shortest distance between two points is a straight line. The attack line is the straight trajectory an assailant’s weapon follows in movement toward the target (you). Remaining on this path places you at extreme risk, as it allows the attacker to maintain momentum and continue his attack. Stepping to the side, diagonally forward or even behind the attacker(s) forces them to readjust their assault, momentarily disrupting their OODA loop and attack rhythm, providing you with an opportunity to counter, escape or gain a tactical advantage.

In close quarters, you will need to buy time to draw your defensive firearm. Defensive measures against an edged weapon, such as using a jacket as a shield, can help here.

Moving off the attack line not only reduces the likelihood of being struck, but also enhances the defender’s ability to control the encounter. Angling away can place you in a position of dominance, allowing you more time to access your defensive tools, use leverage for takedowns or push the attacker into an obstacle.

Additionally, changing position forces the attacker to constantly reorient, potentially breaking their balance and limiting their ability to deliver effective or even successive strikes. By actively controlling distance and position, you maximize your survival chances, turning an otherwise lethal encounter into a winnable fight.

Staying mobile in any self-defense scenario, particularly against an edged-weapon attack, significantly increases your chances of survival. Movement forces the attacker(s) to constantly adjust, making it more difficult for them to land effective strikes.

A stationary target is easy to track and overwhelm, whereas a moving defender disrupts the attacker’s timing, forcing them to react rather than act with precision. By continuously shifting position, changing angles and adjusting distance, when possible, you can create openings to escape or counterattack. Mobility also allows you to exploit obstacles, using environmental elements such as walls, furniture or vehicles to slow the attacker down, limit their striking options and create opportunities for disengagement.

Mobility is directly tied to survivability because a moving target is much harder to hit than a stationary one. This principle applies across all forms of combat, from hand-to-hand engagements to firearm and edged-weapon encounters. Effective movement—whether through lateral steps, pivots or dynamic footwork—ensures that an attacker must continually reset their approach, giving the defender critical moments to strategize, evade or neutralize the threat.

Controlled movement also helps maintain balance, preventing you from being easily knocked down or trapped in a compromising position. By integrating movement into defensive tactics, a person facing a knife attack significantly enhances their ability to survive, making it far more difficult for the attacker to land a decisive or fatal strike.

Utilizing cover and concealment is a fundamental defensive strategy, not just against firearms, but also against edged-weapon attacks. Many people associate cover primarily with stopping bullets, but solid barriers can be just as effective in slowing down or restricting the movement of a knife-wielding attacker. By placing a physical object—such as a wall, vehicle, furniture or even a large trash can—between you and the threat, you can create an effective time buffer to assess the situation, access your defensive tools and prepare an appropriate response.

Unlike firearms, knives require close contact to be effective, meaning that any obstacle forcing an attacker to take additional steps or navigate around increases the reactionary gap and the likelihood of successfully deploying your firearm in self-defense.

Beyond creating space, cover and concealment force an attacker to make critical decisions that may expose their weaknesses. If they attempt to go around an obstacle, it buys you time to draw your handgun or find an escape route. If they hesitate, it provides an opportunity to issue verbal commands, prepare a counterattack or move to a dominant position.

Effective use of cover also allows you to create angles of engagement, forcing the attacker into less favorable positions where they cannot easily reach you. While creating distance (running away) is always your best option, when escape is not immediately possible, using cover and concealment as a tactical barrier allows you to fight on your terms rather than being cornered into a reactive position.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply