While the United States Navy continues to operate more aircraft carriers than any other country in the world, the list of other nations that operate or have operated flattop warships is extensive. The UK, China, France, Japan, India, the Soviet Union/Russia, Spain, Italy, Brazil, Thailand, Canada, and Australia are among the current or former countries to have or have had such warships. Turkey and South Korea are currently either building or developing potential drone carriers, while Indonesia is considering the purchase of a former Italian helicopter carrier and converting it for drone operations.

When it comes to aircraft carriers, one significant industrial and military power deserves an asterisk. That is Germany, a nation once renowned for its battleships. However, although it was never completed, during the Nazi era, the Kriegsmarine began construction on the Graf Zeppelin. This aircraft carrier would have been similar in size and possibly possessed the capabilities of the U.S. Navy’s Lexington-class flattops.

The Graf Zeppelin is just one part of Germany’s failed attempts to build an aircraft carrier.

Carrier I

It would be incorrect to suggest that Graf Zeppelin was the only, or even the first, attempt by Germany to build a carrier. It was simply the program that gained the most notoriety, while it also saw the most progress. The first unsuccessful attempt occurred decades earlier during the First World War, when the Kaiserliche Marine (German Imperial Navy) drew up plans to convert an incomplete passenger liner into an aircraft carrier.

Yet, even that isn’t the beginning of the story.

Following the lead of the UK’s Royal Navy, the Imperial Navy had experimented with seaplane carriers before the outbreak of the war. Still, it was universally determined that launching and recovering seaplanes was ineffective.

As military aviation evolved at a rapid pace, nations, including Germany, explored the possibility of launching aircraft from warships. The program was put on hold when World War I broke out in 1914.

It was only in the fall of 1918 that a plan to build a carrier gained momentum. At this stage, no nations were building purpose-built carriers; instead, they were converting other warships or cargo vessels by attaching a short flight deck. The German plan called for converting the ship Ausonia into a carrier. Ordered by Italy before the outbreak of the war, the passenger ship was under construction at the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg. Progress on the liner was halted in 1915 after Italy sided with the Allies, but it was not until October 1918 that the German government seized the unfinished ship.

It was an effort that was far too little and way too late.

The war ended just weeks later, and with the high inflation in Germany and restrictions placed on its navy, the program was canceled. The Italian shipping company refused to accept the ship, and Ausonia was sold for scrap.

Origins of the Graf Zeppelin

In the aftermath of the First World War, some in the German military saw the potential for an aircraft carrier. However, the harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles allowed neither the construction of such a warship nor the possession of military aircraft.

However, even before the Nazis rose to prominence, the German military began to rearm in secret, and that included the creation of “flying clubs.” It was one of several programs carried out in the shadows, which explains how Germany was able to ramp up its rearmament so quickly after the Nazis took power in 1933.

Building a carrier was something that couldn’t be hidden or explained as something other than what it was, and thus, there was no attempt to produce such a warship. Instead, German naval experts watched from the sidelines as other nations, notably the United States and Japan, developed aircraft carriers.

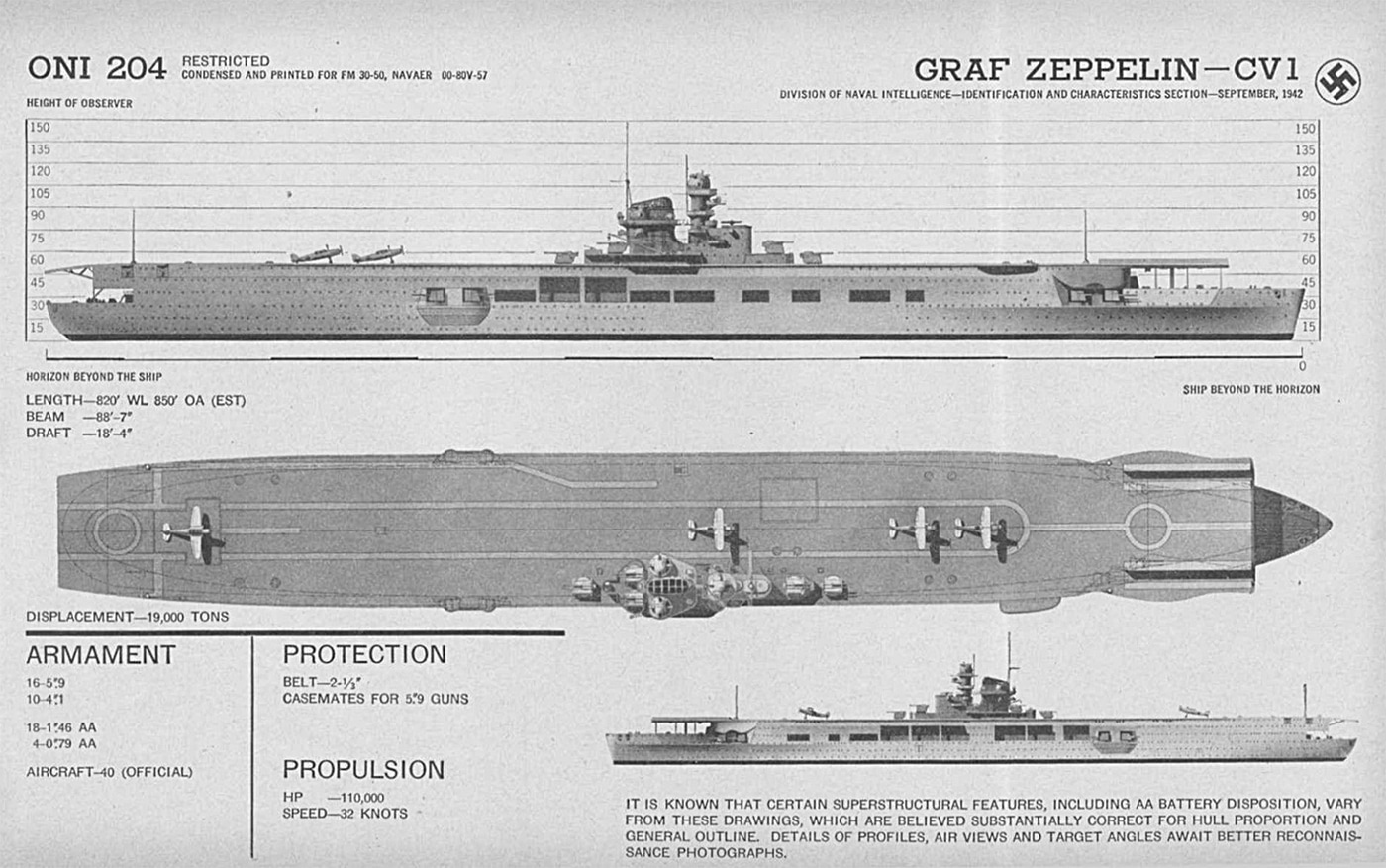

Forward thinkers within the German Kriegsmarine began to consider the merits of a carrier. In 1934, the construction department of the Kriegsmarine authorized a study design for a ship that would displace approximately 20,000 tons, reach a top speed of 30 knots, and carry upwards of 60 aircraft, while also being armed with at least eight 20.3 cm guns. The initial plan also specified that the carrier would have robust anti-aircraft capabilities, along with armor equivalent to that of at least a light cruiser.

For a nation with no experience in naval aviation, having to start from scratch was a daunting task. Complicating matters was the lack of reference material for designers to draw from; instead, the then-operational carriers served as the primary guide. It was with that highly incomplete and entirely insufficient material that 36-year-old naval architect Wilhelm Hadeler undertook the effort to develop a domestically built carrier. Described as a “wonderkind,” Hadeler responded with a plan for a 22,000-ton ship that could carry 50 aircraft.

There was an unforeseen problem.

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935 also allowed Germany to build warships equal to 35% of the total of British tonnage in each category, which Hadeler’s design exceeded. The Kriegsmarine responded by calling for two carriers of 19,500 tons each, which was allowable. That also proved easier said than done, as Germany had no experience to draw from. Instead, at one point, the German design team had a pair of engineers participate in the formal delegation visiting the UK’s “Navy Week,” where they were able to gather insights and even snap a few photos of the Royal Navy’s aircraft carrier, HMS Glorious.

The German design team hit a few other snags as the design continued — notably disagreements over the role of the carrier’s guns. Some still favored additional firepower, failing to see that the great offensive weapon of an aircraft carrier wasn’t its guns, but its aircraft. The Luftwaffe, which had gained prominence as the third branch of the Wehrmacht, was undergoing its own massive expansion and was initially unable to collaborate; however, when it finally became involved, it added more debate on the direction the design should take.

Insight from Japan

Though Germany was able to covertly glean insight into carrier design by viewing the Royal Navy’s carriers, it was Germany’s future allies that provided far more valuable information. In the fall of 1935, the Imperial Japanese Navy allowed a German commission to observe the aircraft carrier Akagi, while the commission was also provided with approximately 100 special plans that included details of the flight system.

There were some surprising discoveries. For one, the Germans were convinced of the need for catapults, which the Akagi lacked. The plans provided some helpful insights, notably the placement of elevators to access the hangars located below the flight deck.

More importantly, it made clear the German designers were on the right track.

The Never-Completed Carrier

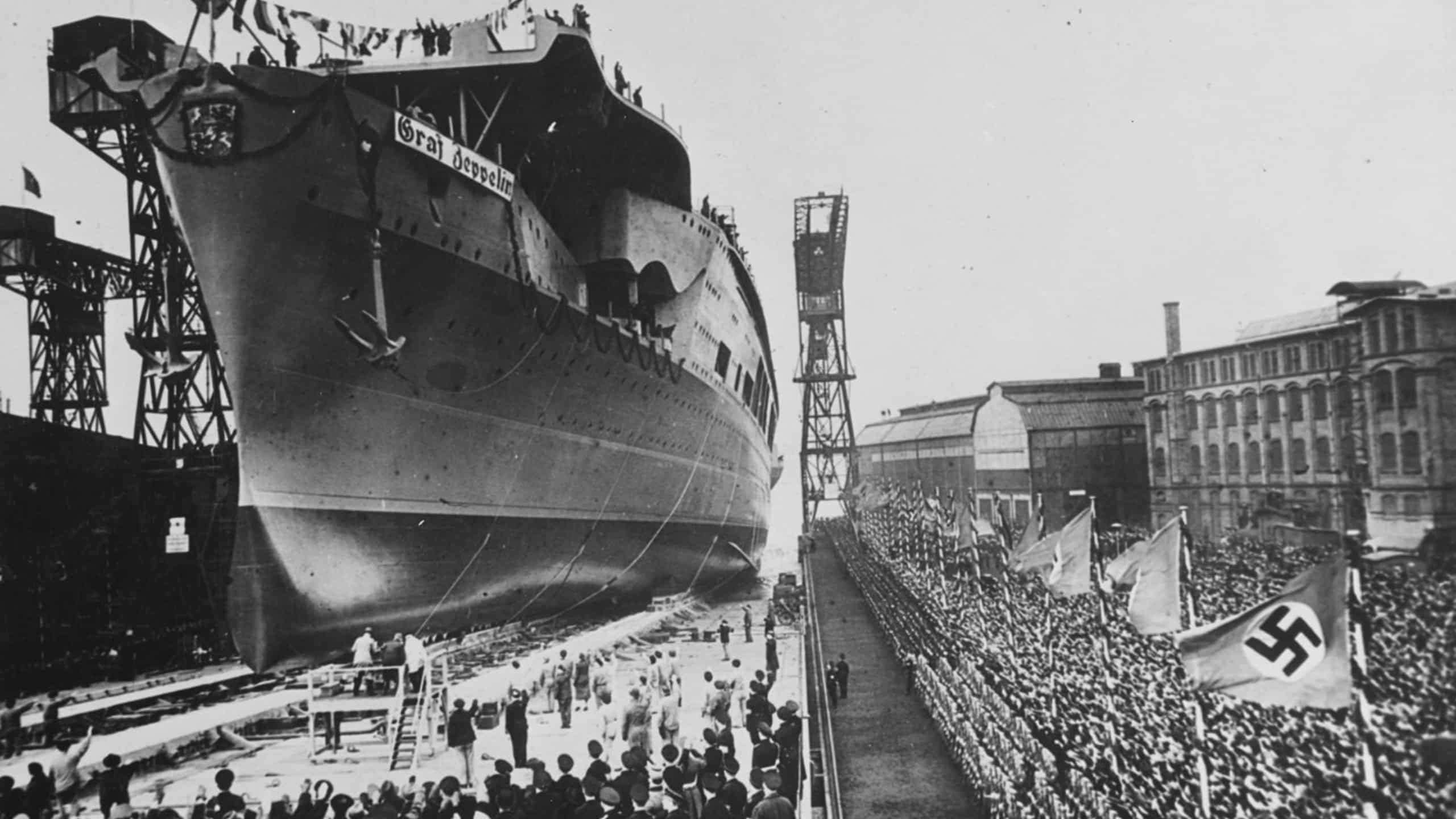

The design was approved near the end of 1935, and it was a year later, on December 28, 1936, that the keel for Germany’s planned aircraft carrier was laid on Slipway 1 at the Deutsche Werke shipyard in Kiel, Germany.

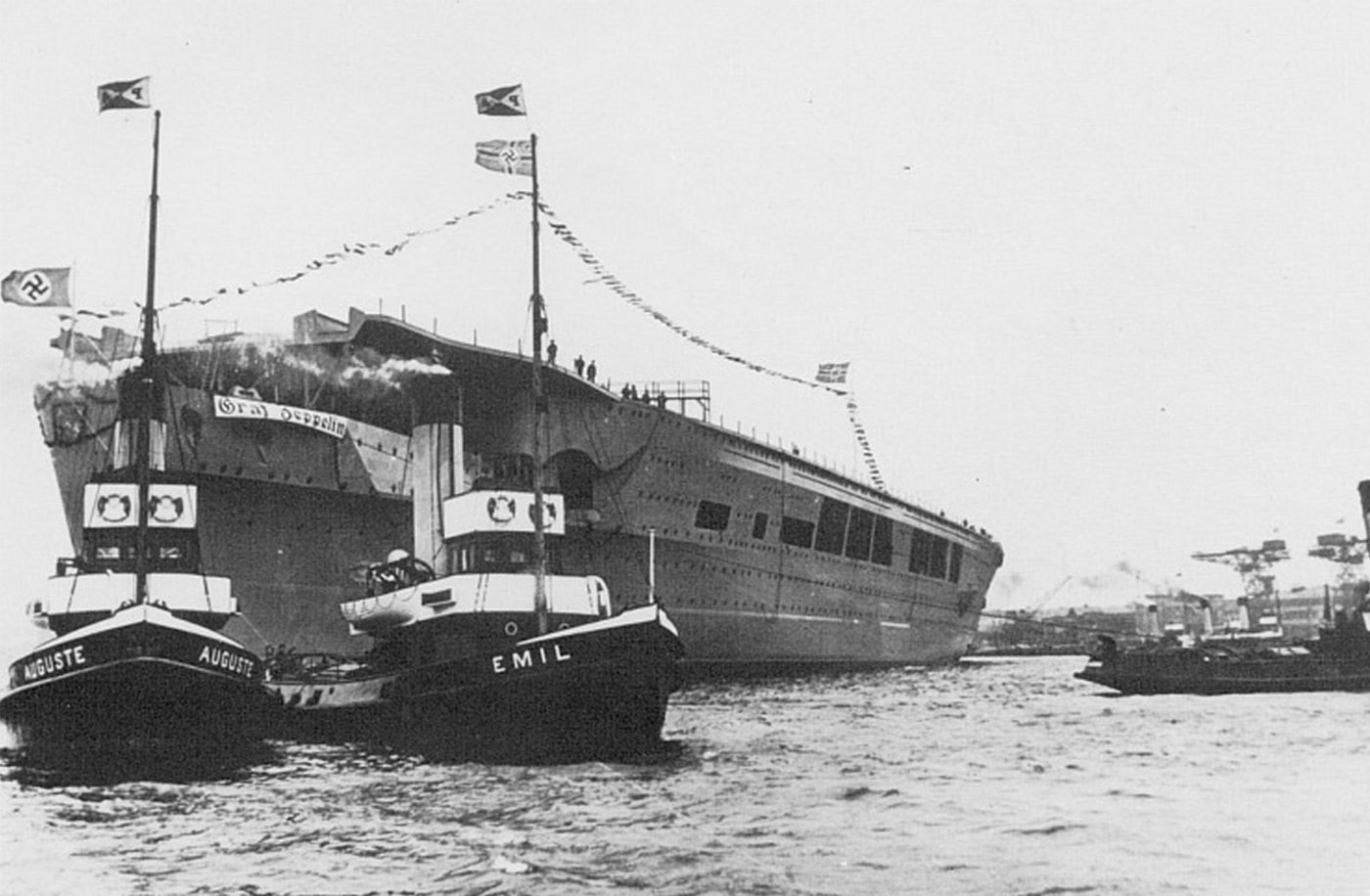

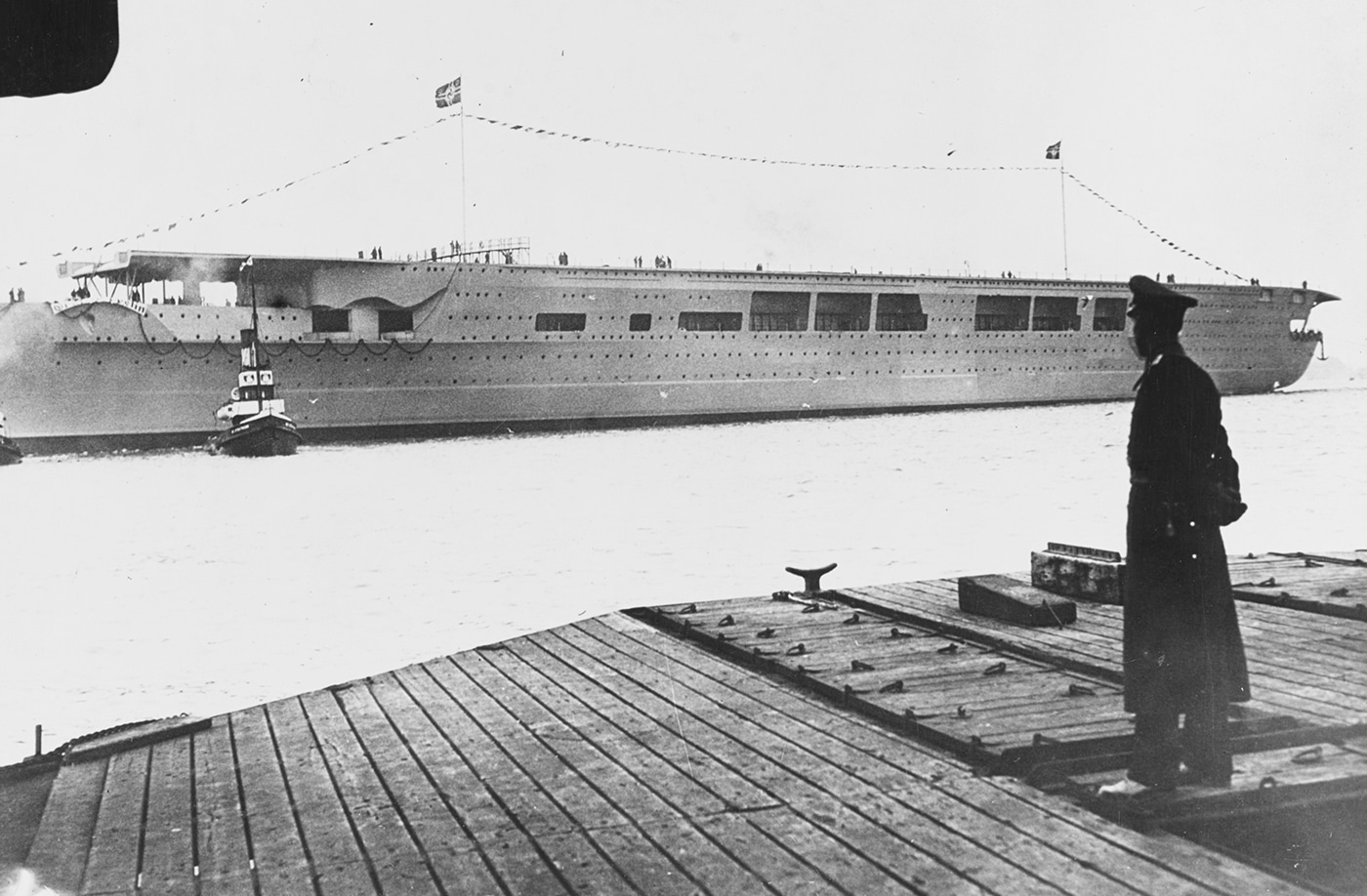

Almost two years later, on December 8, 1938, the warship was launched and christened the Graf Zeppelin, named to honor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, the inventor of the rigid airships known as zeppelins. Helene von Zeppelin, daughter of the count, had the honor of christening the carrier.

Construction on the warship continued at a rapid pace, and it was approximately 85% complete when Germany launched its invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, thereby igniting the Second World War. Original projections called for the carrier to be completed by the middle of 1940, and Trägergruppe 186 had even begun to form as a carrier-borne wing. It was comprised of three squadrons of Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters and Junkers Ju-87 dive bombers.

Although construction continued throughout the fall of 1940 and into early 1941, the German invasion of Norway led to the project being put on hold. In addition, the carrier’s 15 cm guns were removed and transferred to other units, while the heavy flak armament was also diverted to different uses.

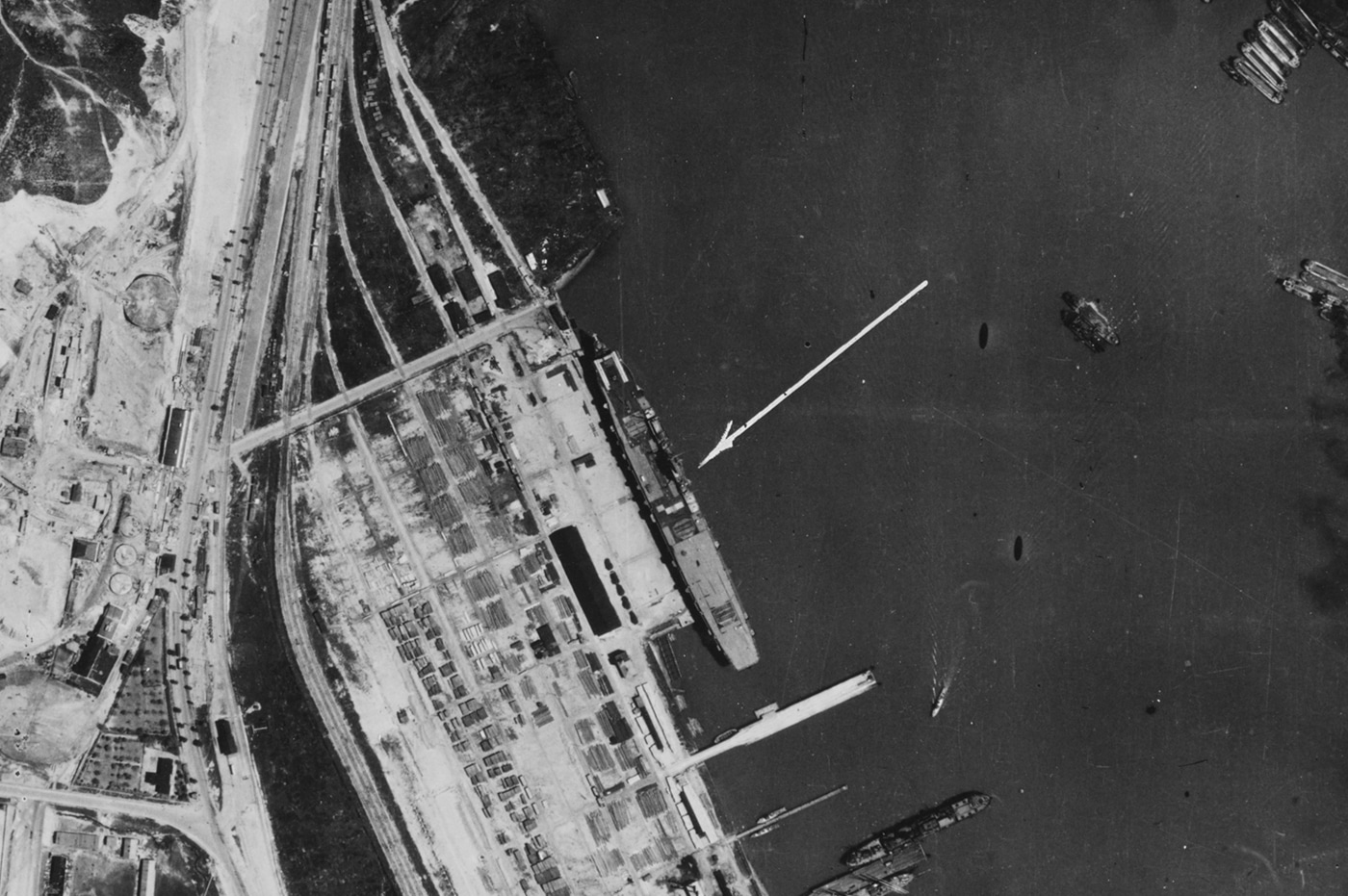

In July 1940, the nearly completed carrier was moved from Kiel to the port of Gotenhaften (today Gdynia) in what was East Prussia. The move was made to keep the warship out of range of British bombers, and while in the port, the vessel was used as a storage depot. Just before Germany launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Graf Zeppelin was relocated to Stettin to safeguard the carrier from Soviet air attacks. However, as Germany advanced deep into the Soviet Union, the ship was again moved to Gotenhafen.

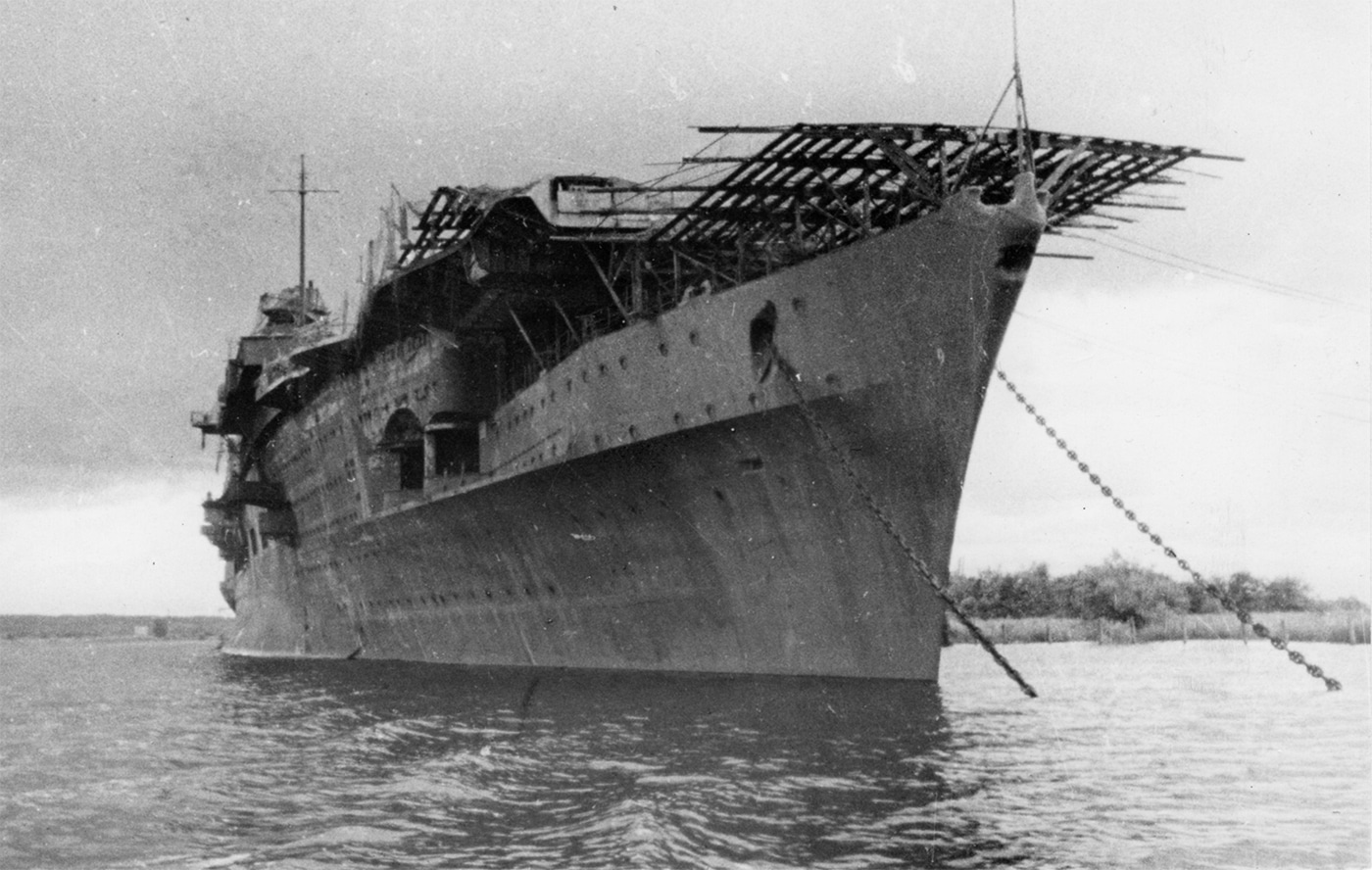

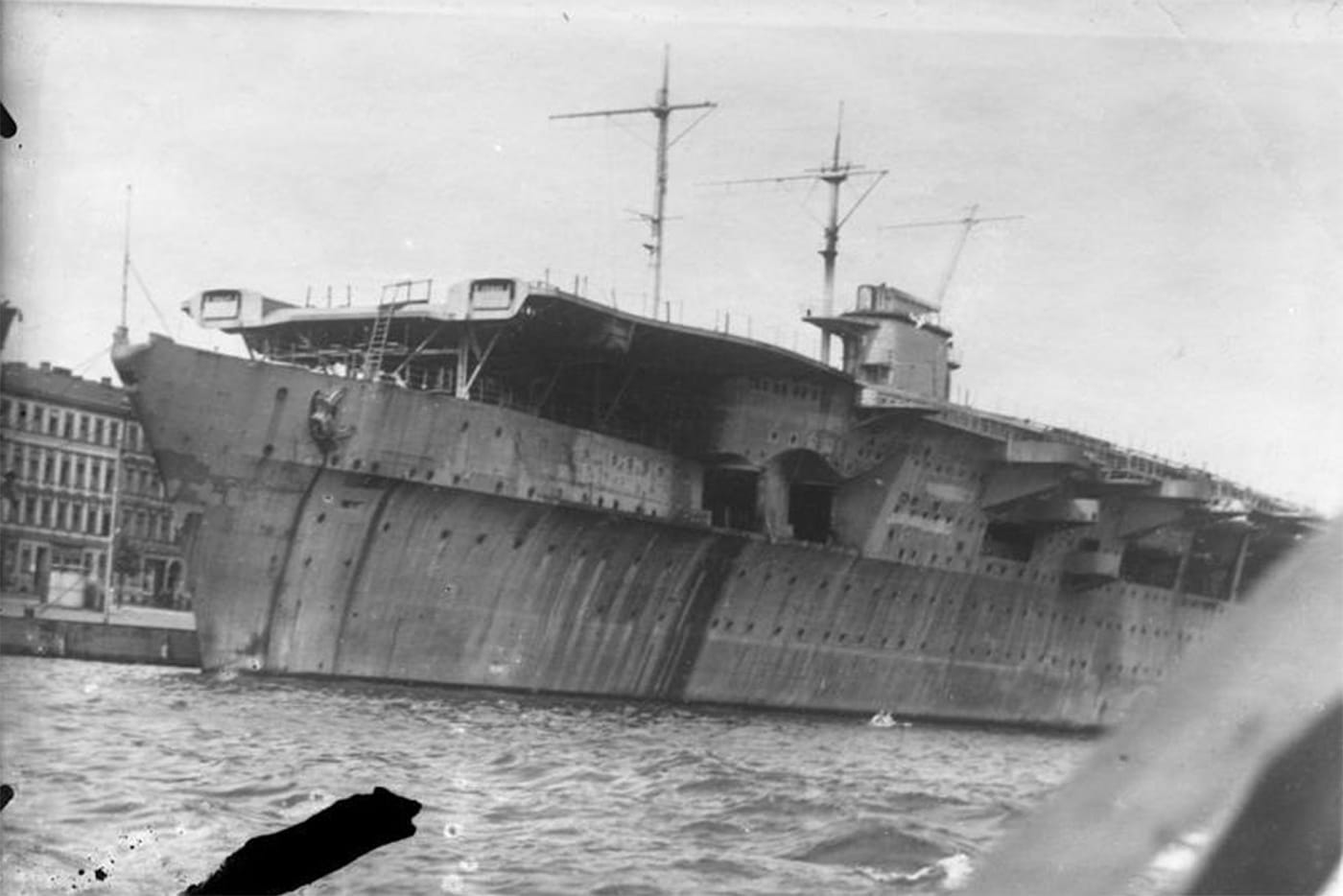

The Royal Navy’s raid by carrier-based aircraft on the Italian fleet in port at Taranto in November 1940, and the subsequent Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, resulted in renewed interest in the carrier, and work then resumed on Graf Zeppelin. Pilot training also continued, but even as it became apparent that newer carrier-based aircraft were needed, the Luftwaffe made it clear that it couldn’t accommodate such a plan. Instead, Germany’s carrier would have to make do with modified Bf 109s and Ju 87s, but those aircraft were heavier than the land-based version, which necessitated design changes to the carrier, including upgraded catapults, more potent winches for the arresting gear, and a reinforced flight deck, elevators and even hangar floors.

Progress on completing the Graf Zeppelin continued throughout 1942, but in early 1943, Adolf Hitler’s opinion of the need for the warship changed again, and he ordered all work halted. Focus was directed to Germany’s U-boats, and work on surface ships ceased.

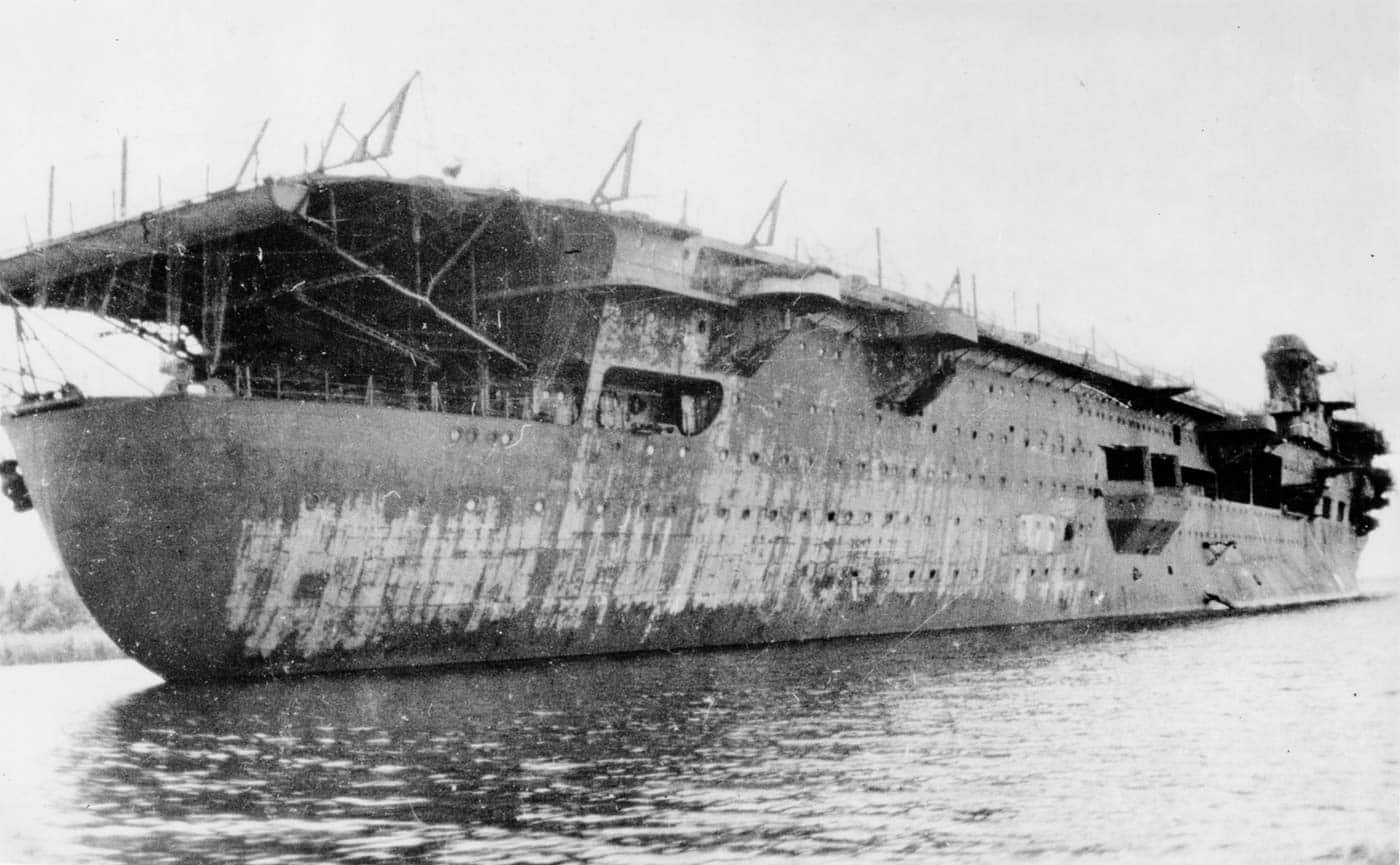

Graf Zeppelin was moved to a wharf outside of Stettin, and throughout the rest of World War II no further work was completed. Although 90% complete, the Kriegsmarine’s aircraft carrier never went to sea under its own power and instead was scuttled in port at the end of World War II to prevent the ship from being captured by the Soviet Red Army.

Though the Germans attempted to ensure that Graf Zeppelin couldn’t be repaired and put to sea, salvage specialists from the Soviet Navy worked feverishly to raise the ship. It took until March 1946 for the carrier to be made watertight and capable of floating again.

There have been conflicting reports on exactly what happened. After the carrier was refloated, an attempt was made to tow the vessel to Leningrad (St. Petersburg), with her hangars reportedly filled with looted goods, including German machinery.

The official story has been that the ship struck a mine in the Gulf of Finland and sank. However, another claim is that the Graf Zeppelin did, in fact, make it to Leningrad and was broken up as scrap with Soviet destroyers sinking the remaining hulk in torpedo drills. The former outcome seems likely, as a wreck, believed to be that of a German aircraft carrier, was discovered by the Polish Navy in July 2006.

Not the Only Carrier

Another part of Germany’s carrier ambitions history is that the original plans called for four Graf Zeppelin-class vessels, which were later scaled back to just two. Moreover, a second ship of the class, the Flugzeugträger B, was also ordered with construction beginning in November 1935. Work on the second carrier proceeded slowly, so that it could take into consideration any experience gained from the Graf Zeppelin.

By the time war broke out, the lower framework had only risen to the platform deck, and it was far from reaching the launch stage. As a result, work was halted and the unfinished ship was scrapped.

Germany’s brief interest in carriers, notably after the loss of the battleship Bismarck, resulted in plans being drawn up to convert the passenger ship SS Europa into a carrier. At the same time, the Norddeutscher Lloyd steamers SS Potsdam and SS Gneisenau were selected for conversion to auxiliary carriers. The former was to be renamed Jade, while the latter was to be renamed Elbe. Very little progress was made on these, and both programs faced numerous challenges. The most significant design challenge to emerge was that the flight deck would have made each of the vessels top-heavy and unstable. Solutions reportedly included placing ballast within the ships, or in the case of Elbe, an outer hull would have been added. Construction on all three halted along with that of the Graf Zeppelin.

Germany also began converting the final Admiral Hipper-class cruiser, renamed the Wesser. Work started in early 1942, which included the removal of her superstructure. The project also ended in 1943, before the flight deck was installed. An incomplete French cruiser, De Grasse, was also considered for conversion. However, there was no available workforce, and the program never moved forward.

Were Carriers Even the Right Direction for Germany?

Though not completed, the Graf Zeppelin was considered a reasonably capable design. It featured 19 watertight compartments, which would have allowed it to endure significant damage in combat, while its turbine system may have given it considerable speed, making it perhaps the fastest carrier of its time. Moreover, unlike most other carriers of the era, it was to have an armored flight deck and a substantial number of anti-aircraft guns.

At the same time, it wouldn’t have been able to carry a significantly large number of fighters while the Kriegsmarine lacked the surface vessels to serve as her escorts. The ship’s greatest Achilles’ heel was the lack of an adequate fighter designed for naval operations.

It is true that in the early stages of World War II, a German carrier, even with Bf 109s and Ju-87s, would have an advantage over the Royal Navy’s carriers that still depended on the hopelessly outdated Fairey Swordfish bi-planes.

Yet, the question is, what was the goal of the carrier program?

In the Pacific, carriers provided vital support during America’s island-hopping campaign, whereas in the Atlantic, they provided air cover only for the landings in North Africa and the invasions of Sicily and Italy. By contrast, however, the D-Day invasion largely didn’t employ carriers. The only flattops involved in Operation Overlord were from the Royal Navy, with the warships engaged in anti-submarine operations. The primary air support for the Normandy landings came from land-based aircraft in the UK.

The most significant mission for the Kriegsmarine in the Battle of the Atlantic was commerce raiding and striking Allied convoys. The surface fleet proved far less successful at it than Germany’s U-boats. The carriers likely wouldn’t have been considerably more successful than Bismarck and Germany’s other surface raiders.

Moreover, without escorts, the carrier would have been in the crosshairs of the UK’s land-based fighters and bombers. At best, the Graf Zeppelin would have required the U.S. Navy to devote additional attention to the Atlantic to deal with Germany’s carrier.

It is thus understandable that Germany gave up on carriers when it did, but the bigger question is why it ever bothered in the first place!

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply