For as long as I can remember, the guys at my range were what I’d call “knife people.” I always liked what they were carrying, but was reluctant to spend “gun money” (or hell, even ammo money) on a pocket knife. I had about three designs I generally thought worked well enough for me, and that was that. Of course, it was only a matter of time before I got bit by the bug, and my collection of knives has since ballooned from three examples to something well north of 100.

Many readers might still think similarly to how I did years ago — which is to say, “a knife is a knife.” Follow that line of reasoning ever further, and the kind of inexpensive knife you’d find at the gas station or hardware store should be just as good as one costing $200, right?

[Check out Mike Boyle’s article Fixed Blade vs. Folding Knife for a look at what to think about when selecting an EDC knife.]

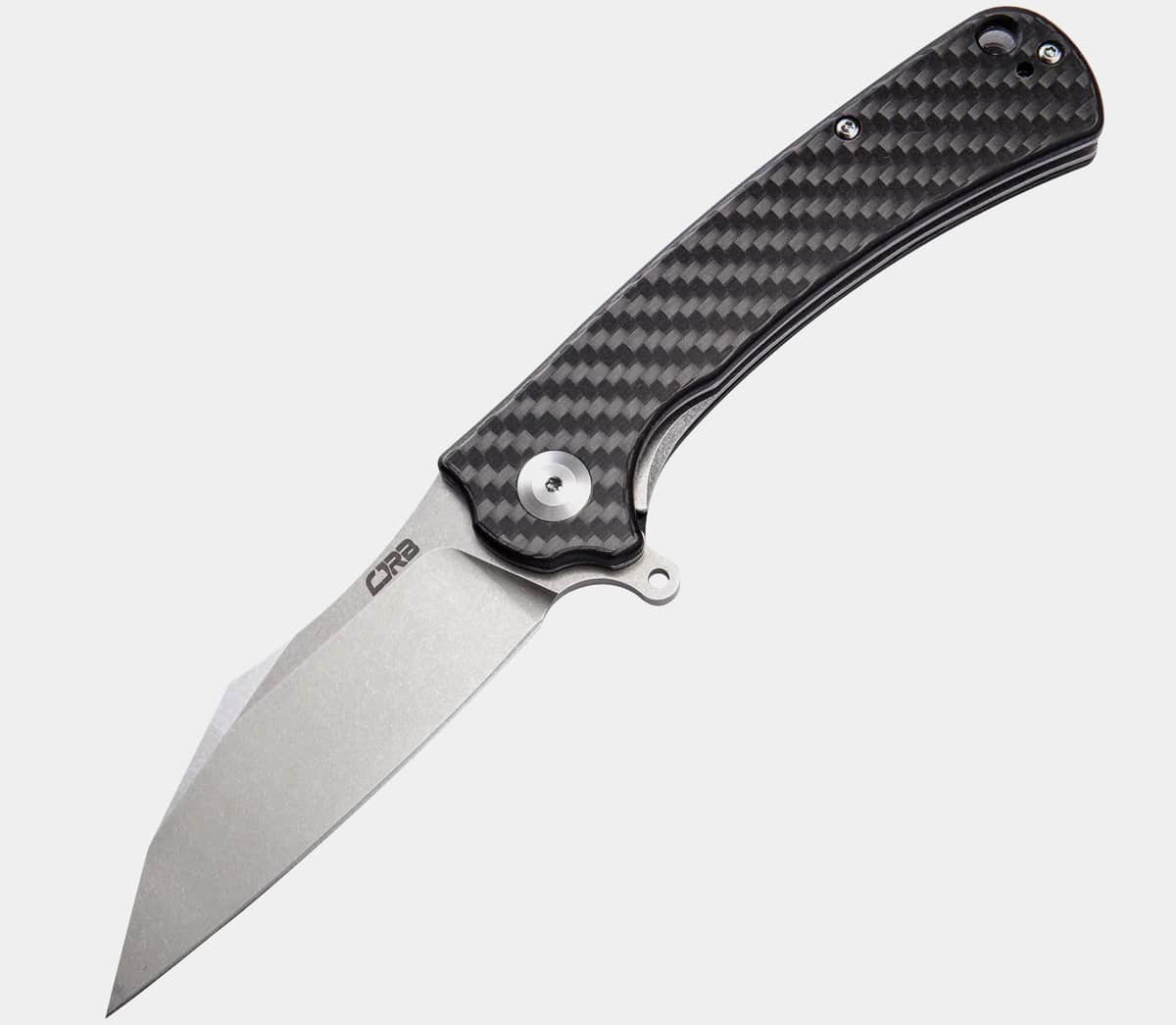

Well, today, let’s see exactly where the money goes. I’ve pulled out a few knives from my own collection that I think represent outstanding value and quality (all can be sourced for less than $60). Let’s compare them to the $8 knife I bought right from the hardware store.

The Blade

Let’s start with the most important part of the knife: the blade itself. It’s been a good time to be a consumer over the last 20 years, as manufacturers have increasingly spent time not only on developing steel compounds that are more wear and corrosion-resistant than ever before, but have competed against one another to get better and better steels into their knives at progressively lower prices.

As a general rule, if a knife is using a steel worth mentioning, they’re going to mention it. With common compounds like D2, AUS-8 and 14C28N, the consumer can easily google the relative strengths and weaknesses of these alloys to determine what best fits their needs. D2 holds an edge really well, but can rust more easily than other compounds; not a great choice for someone on a boat. AUS-8 has great corrosion resistance and is easily sharpened, but has less edge retention; it’s a great all-around steel for EDC use and household work.

A gas-station level knife isn’t going to mention what it’s made out of. Beware of anything that simply says “stainless steel” — or “surgical steel,” which sounds flashy but really signals it’s likely going to be junk. These edges typically wear like butter, and often have difficulty holding an edge in the first place.

If you buy a quality knife from a good manufacturer, it may arrive hair-shaving sharp, but almost always it will have a good enough factory edge to cleanly slice through printer paper without ripping. My $8 knife did neither, but had enough sharpness to catch a fingernail. That said, whatever middling amount of sharpness the blade had dulled considerably after cutting through about 14 linear feet of cardboard. In plainer terms, it was toast in about three minutes of honest work.

The Materials

Modern knife manufacturers have bent over backwards to develop excellent compounds suited to a variety of user needs. Micarta, a layered paper-like material, looks great and provides excellent texture, wet or dry. Carbon fiber is extremely strong and contributes excellent weight savings. And, for not very much extra money, those who prefer a heftier feel to their knives will find aluminum, stainless steel and titanium frames.

At the sub-$50 level of most quality manufacturers, you’re going to find a lot of G10, a compound made of epoxy and fiberglass. G10 isn’t cheap — it’s inexpensive. Easily milled and shaped, G10 has excellent strength, temperature resistance, insulation from heat and electricity, and is naturally water-resistant. It also has a good texture that stays put in the hand, not unlike a high-grit emery board. G10 can also be milled to make it even more grippy.

On the other hand, my hardware store knife is all kinds of plasticky. Especially cheap compounds have a tendency to crack or shatter under even moderate levels of stress or hard use. New, the material is slick to the touch. Over a period of years, the rubber and plastic materials on the handle often get sticky and gross. The cheap steels used for the pocket clips can easily be bent out of position or sheared away entirely. The good news, if there is any, is that you’re unlikely to lament the loss of your $8 knife if the clip breaks, or if the spring tension doesn’t adequately secure it when you’re out and about.

Safety

A knife you trust for hard use should have some good passive safety features and baked-in durability to ensure it won’t break or fail under hard use. Or hell, even moderate use.

On a quality knife, lock-up is positive and secure, and locks are often designed to withstand several hundred pounds of force. There are trade-offs here related to strength, quality and ease of operation, but in general a good manufacturer will produce a knife that is solid when deployed and remains locked during hard use, if not outright abuse.

[Also see Clayton Walker’s article on folding knife lock types for additional information.]

While my advertised knife was billed as being a liner lock design — and while it certainly seems to have a lock bar — I was surprised to find that the liner didn’t actually engage with the base of the knife when opened fully. In fact, I needed to hyper-extend the knife blade to get the lock bar to click into position. I would add this was only possible due to the play provided by the plastic materials.

Suppose someone was actually to use this for a job requiring a reasonably tough material to be punctured. I’m not talking trying to stab this thing through a car hood — let’s just say that the task of the day requires poking through relatively thin PVC or plastic tubing. Without the lock engaged, and with the knife being pushed and wiggled, it’d be very easy to see how this thing could close right on a person’s fingers!

Of additional interest is the stop pin, which is intended to prevent backwards rotation of the knife blade in the full open position. On my cheap knife, it’s made of plastic and molded into the handle. I didn’t think it would take much force to shear that piece off completely if I was bearing down on the knife. Indeed, with relatively light pressure breaking down that single cardboard box, that’s exactly what happened.

Picking Nits?

Let’s be honest: while I certainly didn’t expect the “cheap” knife to perform well, I didn’t cherry-pick the worst knife I knew of. This thing was new in the box, and I tested and photographed the very tool handed to me by the hardware store clerk. And, after trying to use it for one relatively easy household job, the knife broke on me.

Superficially, my $8 purchase fits the dictionary definition of a knife. However, if we create even a modest set of expectations as to what a knife should be able to do, or a list of criteria of how we’d fairly judge a knife, the $8 wonder was a dismal failure across all accounts. It didn’t cut well out of the box, and then rapidly deteriorated in its performance before it broke entirely. At that point, a Spyderco Manbug — diminutive though it may be, but unquestionably a real knife — came out of the fifth pocket of my jeans to finish the job.

Again, you don’t need to spend gun money on a knife. But, you probably can stand to spend about $30 to $50 on a good one, and just about any design from CRKT, Kershaw, Civivi, CJRB, Schrade, SOG, Kizer, Gerber, Cold Steel or Spyderco within that price point will treat you right. (A list that is by no means exclusive!)

If you’re still on the fence, give one of the “real” knives featured above a try. I’m willing to bet it will replace whatever cheap, no-name blade you might be putting to regular use.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Read the full article here

![Best Tactical Lever-Action Rifles [Field Tested] Best Tactical Lever-Action Rifles [Field Tested]](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/tactical-lever-action-rifle-feature.jpg)

Leave a Reply