The Japanese military showed little interest in submachine guns (SMGs) throughout the 1930s and well into World War II. When the Emperor’s men finally began to produce a home-grown SMG in any appreciable numbers during 1944, the opportunity to compete with their opponents’ short-range firepower was lost.

During the 1920s, the .45 caliber Thompson submachine gun became a dominant influence on a new category of infantry weapons. In Europe, weapons like the Bergmann and the Solothurn were popular (chambered in 9mm among others), albeit expensive. Improvements were made to Germany’s World War One MP18, creating the MP 28. All of these SMGs were popular in China, as well as the fully automatic version of the Mauser C96 pistol (and its Spanish-made clones, and Chinese-made copies).

The Japanese made no move to create their own submachine gun during the 1920s, but they did import the M1920 (Brevet Bergmann, a Swiss-licensed built version of the MP 18) in 7.63x25mm. The Japanese also purchased small amounts of the Steyr-Solothurn S1-100 (better known as the MP 34), but altogether the total amount of SMGs they imported from Europe was less than 10,000.

Despite the small total, these weapons were used by Japanese military troops (particularly the Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces of the Imperial Japanese Navy land forces — similar to the United States Marines) during the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, and then during the Second Sino-Japanese War with China beginning in 1937. During this time, the Japanese captured small amounts of Bergmann M1920 SMGs from the Chinese and incorporated them into their arsenal.

While the Japanese used their European-import SMGs successfully during the war in China, their own efforts to design and produce a submachine gun lacked energy and direction. Close-quarters urban combat in the Battle of Shanghai during 1937 showed that Japanese troops needed greater infantry firepower, particularly light machine guns (LMGs) and SMGs. The Bergmann and Solothurn guns were excellent, but they were quite expensive.

Enter the Type 100 Submachine Gun

Consequently, the Japanese reexamined their needs, and set out to create their own, simplified Bergmann-type SMG. This was developed at Nambu Arms in late 1937 and called the Experimental Model 3 submachine gun. It was introduced in the spring of 1939. Japanese military actions continued to intensify, and once again the SMG development lagged. With World War II in full swing and Japan at war with the Allies, the Nambu submachine gun was finally adopted as the Type 100 during early 1942.

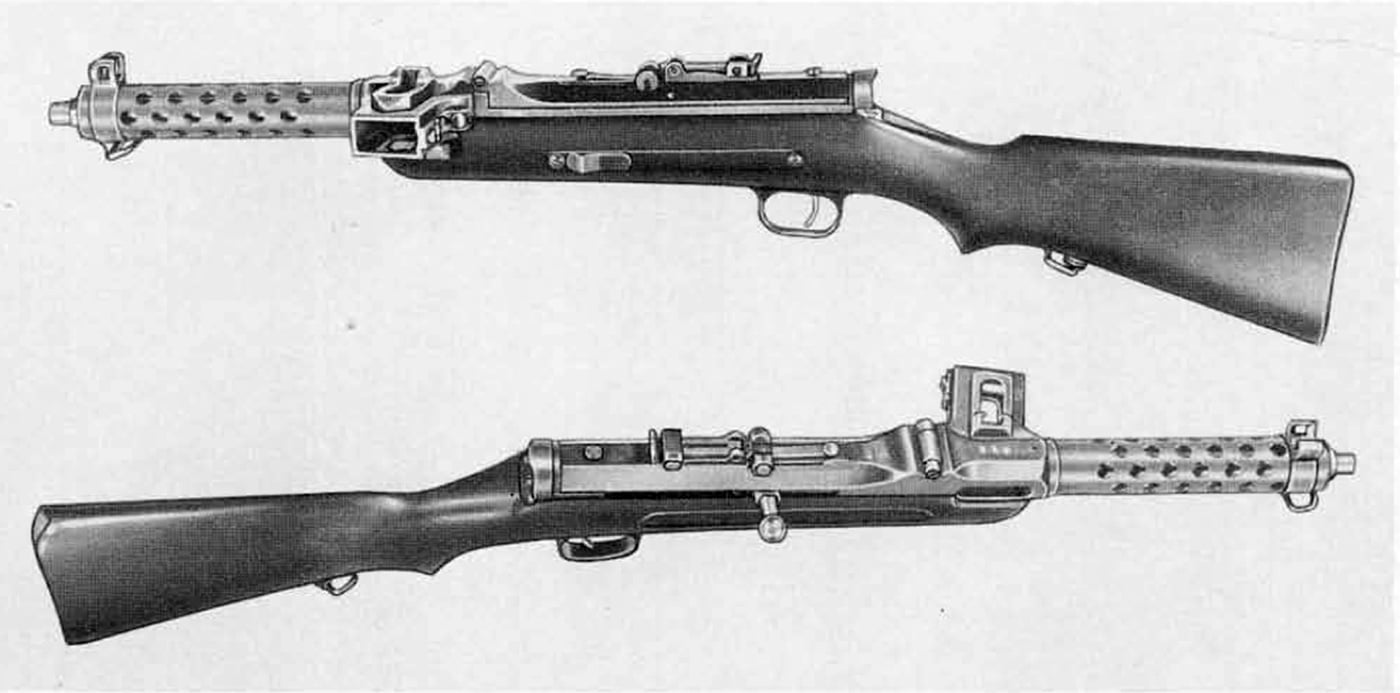

The Type 100 is a simple blowback design, operating only on full-auto, and firing from an open bolt. The firearms were chambered for the Japanese 8x22mm Nambu pistol cartridge. The 30-round magazines are reliable, using a double-stack, double-feed system. There is a combination muzzle brake and compensator fitted to the cooling jacket.

The initial Type 100 guns featured an adjustable sight, marked up to a wildly optimistic 1,000 meters! Other early features included a folding bipod, as there were some notions of using the SMG as a squad automatic weapon. At the same time, with the Japanese devotion to the bayonet, the Type 100 was fitted with a stout, tubular bayonet lug beneath the perforated barrel jacket. A small amount of Type 100s were captured by U.S. troops on Guadalcanal.

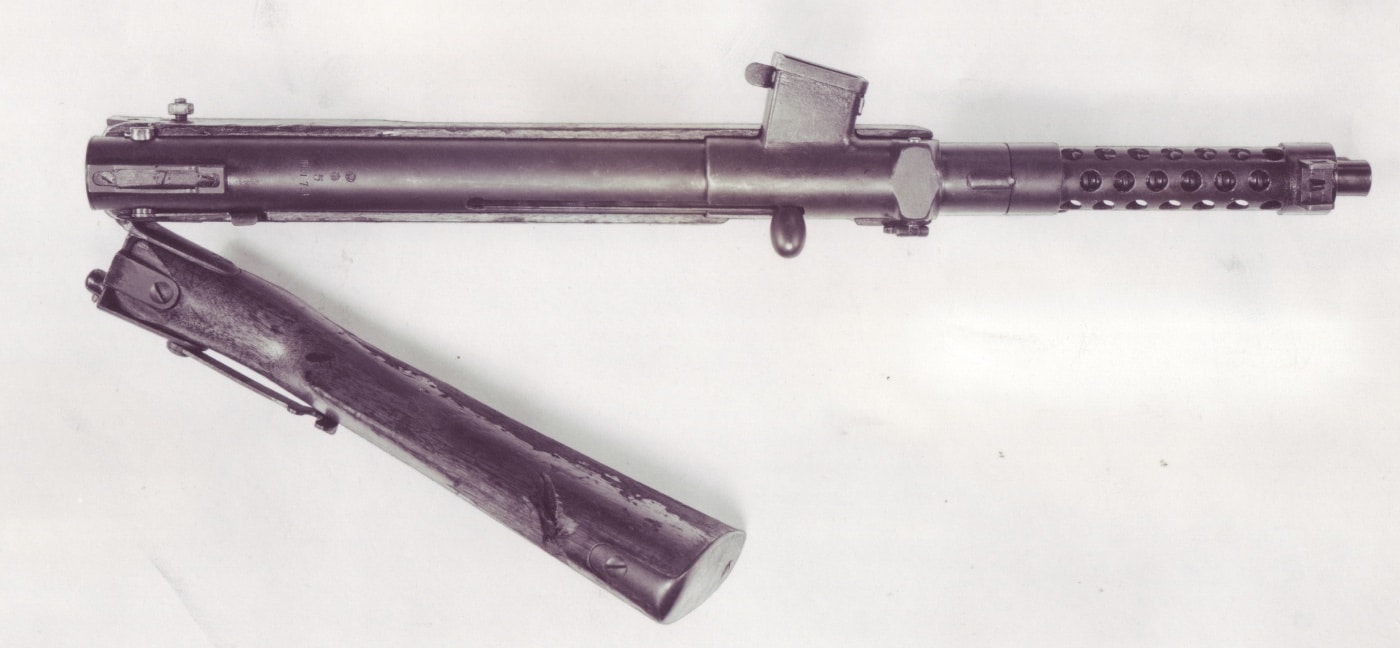

The most unique variant of the Type 100 was produced early on — a paratrooper version with a folding wood stock. Japanese paratroops of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service conducted early operations by dropping the weapons in separate cannisters — leaving the paratroopers dangerously unarmed for at least a few critical moments. To correct this, the Type 100 could be folded and carried in a special belly pack. A few of these folding stock guns were captured by U.S. troops on Luzon during the Philippines campaign in 1944-45.

Updated — Type 100/44 SMG

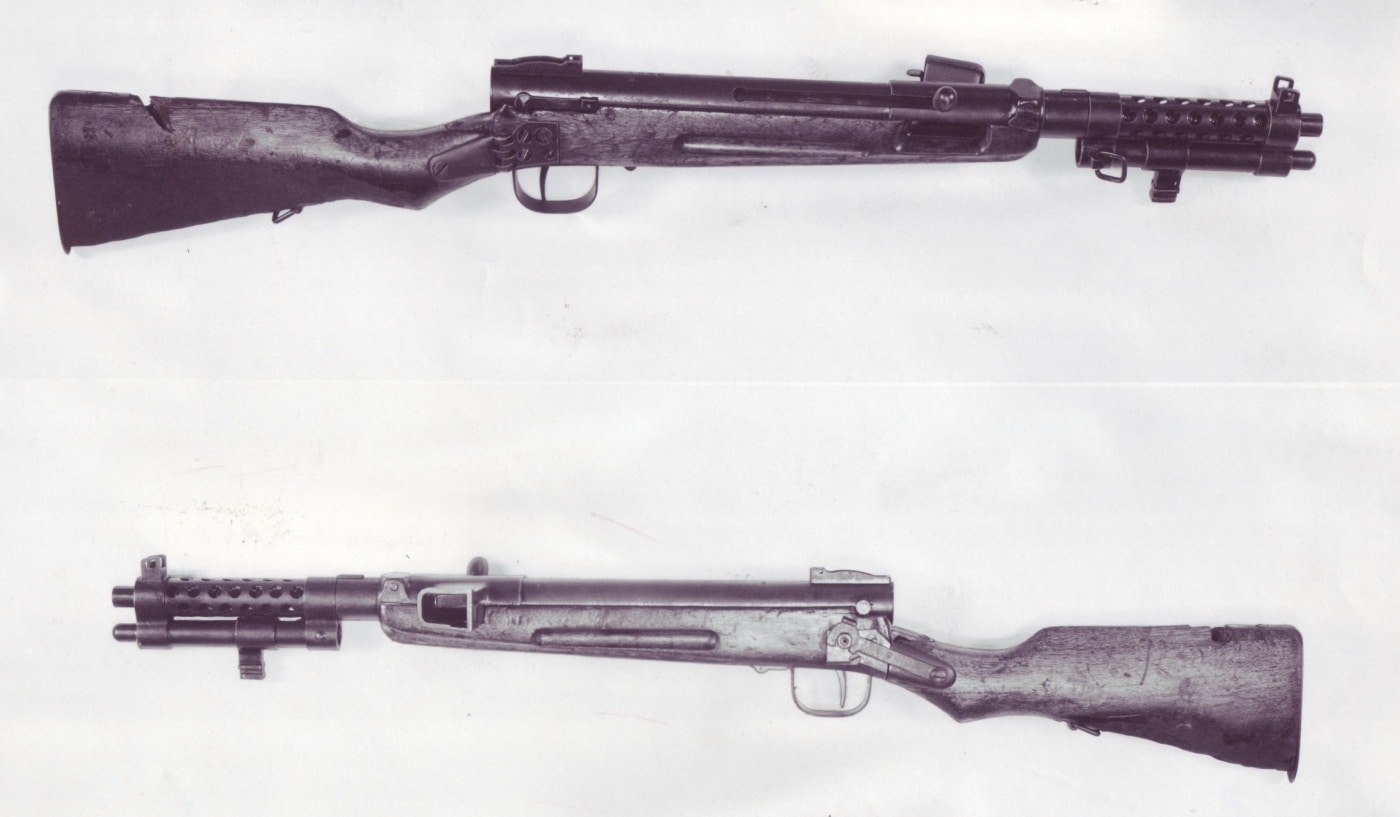

By 1944, the Japanese need for SMGs had quickly overwhelmed the tiny production of the original Type 100s. To speed up production and reduce costs, the Type 100 was simplified: basic iron sights with a rear peep were fitted, the large bayonet mount was eliminated, and the muzzle brake became two ports drilled into the muzzle. Many examples of the later Type 100 showed very rough finishing. Even so, the gun performed well, and the cyclic rate nearly doubled from 450 to 850 rpm.

On the downside, the Japanese 8x22mm Nambu round was never quite powerful enough for an SMG, and as the war progressed the quality of the ammunition degraded noticeably. Despite the revisions, production never ramped up to the level desired, and by the end of the war only about 10,000 Type 100s were produced in total.

The Type 100/44 versions were notably used by Japanese Teishin Shudan in the Philippines 1944-45, and by the Giretsu Kuteitai suicide commandoes during the Raid on Yontan Field on Okinawa during the night of May 24-25, 1945. Some sources say that Type 100 SMGs were issued to Japanese police by United States occupation forces in the early months after WWII.

This wartime description of the Type 100 comes from the U.S. Intelligence Bulletin, July 1945 edition:

Versions of the 8mm Submachine Gun

Complete specimens of all three known versions of the Japanese Type 100 (1940) submachine gun are now in Allied hands. The three versions thus far identified are:

(1) the earliest version with removable bipod and bayonet

(2) the paratroop version, with removable bipod, bayonet, and folding stock

(3) the latest version, with bayonet but no bipod

It was known prior to the capture in Burma of the earliest version that this unusual weapon was fitted with a bipod. Recovery of an actual specimen with bipod reveals that the bipod secures around the barrel jacket by means of a collar. The bipod locks to the tubing below the barrel jacket, thus providing a quick release feature. Inspection of the various guns shows that the paratroop version of the Type 100 can also take the bipod, and that the paratroop gun is identical to the earliest version except for the folding stock. No bipods have yet been reported as having been found on, or near, captured paratroop Type 100’s. Since the bipod is a most unusual addition, the appearance of the third version of the Type 100 without this feature was not at all surprising.

This latest type of Type 100 is fitted to take the standard Type 30 (1897) bayonet, in line with the official Japanese doctrine which urges fighting with cold steel.

Ammunition

Although preliminary tests indicated that Japanese 8-mm pistol ammunition would not function in a Japanese 8-mm Type 100 (1940) submachine gun, further tests now show that such use of the ammunition is entirely practical. In the first tests, caliber 8-mm pistol ammunition packaged for the Type 94 (1934) pistol functioned very badly when used in a later model Type 100. Some 75 percent of the cases failed to extract, while others were badly bulged. However, tests with other Type 100 guns now show that the performance with ordinary Japanese pistol ammunition is entirely satisfactory. It is presumed that the Type 100 first tested was defective.

In spite of modification of the Type 100 series to the latest form, this type of submachine gun leaves much to be desired. For one thing, it represents a manufacturing problem. The Japanese have made no effort to ease production bottlenecks by the extensive use of stampings throughout the weapon. They have manufactured a Bergmann-type gun, instead of one patterned after the mass-production German “burp gun,” the M.P. 38 (1938). From the operational point of view, U. S. Army Ordnance tests indicate that its cyclic rate of 800 to 1,000 rounds per minute is too high for maximum effectiveness. U. S. Army findings in this respect are bolstered by the experience of other battle-tested armies. German submachine guns have a rate of fire around 500 rounds per minute. The Red Army, which in its P.P.D. (1940) and P.P.Sh. (1941) guns had weapons with a 1,000-round per minute cyclic rate, later standardized on their M1943 submachine gun with a cyclic rate of 650 rounds per minute. To correct the drawbacks inherent in a high rate of fire, the Japanese have fitted a type of compensator to the latest version of their Type 100.

WHB Smith described the “Submachine Gun Type 0” in his seminal “Small Arms of the World” in 1945:

It was used to some extent by the Japanese Navy and was part of the armament of their paratroop units at Leyte in 1944.

This is an elementary blowback design firing from an open bolt. It uses the standard 8mm pistol cartridge. While many stampings are used, and welding is generously resorted to, it is fundamentally a well-built weapon.

There are two types, one with a standard stock and the other with a folding stock which can be hinged to the left. (Length 49”, barrel 9”, weight about 8.75 lbs. The folding stock type measures 34” with the stock folded.) The folding stock type has a leaf sight of sliding ramp type. The rigid stock design has a non-adjustable peep sight.

The magazine is a detachable box carrying 30 rounds in staggered formation. Rate of fire is about 450-500 rounds per minute. A perforated barrel jacket is employed to aid in cooling and to protect the user against barrel heat. The magazine is inserted in the left side of the action with ejection to the right.

The design is quite simple. The bolt has the firing pin screwed into its face. Full auto only. Trigger safety only.

Cases ejected from guns tested have generally been too badly expanded and dented to permit reloading. The use of “bottlenecked” cartridges in an arm of this type does not give as satisfactory performance as the usual straight-sided cases. Residual pressure is evidently quite high, judging by cartridge case condition and spitting of smoke at the ejection port.

Smith concludes his evaluation with:

Cheaply and simply made, but inferior in most respects to European and American standards.

Hands-On with the Type 100

I was fortunate enough to fire a Type 100 — it was a later type with a higher cyclic rate (about 800 rounds per minute). I am a big fan of full-stock, carbine-style submachine guns, but the Type 100 is not in the class of the Beretta Model 38, the MP 28 or the Steyr, or even the rough PPSh-41. Even so, it is relatively pleasant to shoot and acceptably accurate. I distinctly remember though the odd feeling of the left-loaded magazine emptying and changing the balance of the weapon while firing.

The Type 100 is not a bad gun, but it is not a particularly good one either. Had the war gone on longer or had Japanese SMG development started sooner and with greater intensity, the Type 100 could have made an important difference.

If the Japanese had adopted the 9mm cartridge and copied the German MP 40 or even the British Sten Gun, the Emperor’s troops would have been far more competitive, at least from a short-range firepower perspective, on the battlefields of the Pacific War. As with most things, attitude makes a huge difference, and the Japanese never really embraced the submachine gun concept.

From that perspective, the Type 100 never really had a chance to be one of the great submachine guns of World War II.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply