Col. Townsend Whelen’s reflections on 60 years of experience with his single-shot rifles.

The dean of firearms writers and editors, Colonel Whelen, is the author of many valuable books, notably, The Hunting Rifle and Small Arms Ballistics and Design. His latest volume, Why Not Load Your Own?, is the least expensive and most practical book on handloading available. In this article, he shares with Gun Digest readers his longtime affection for single-shot rifles.

When I was just a little shaver, there was a Winchester single-shot rifle on exhibit in a gun store in my hometown. It was for the 40–82 cartridge, had a 30-inch, half-octagon No. 3 barrel, pistol grip stock of fancy walnut, checkered, Swiss buttplate, target sights, and was nicely engraved. It was my ideal of a fine rifle, and every day after school, while it remained on view, I tramped the 2 miles downtown to admire it. In some such manner are our tastes formed, and they are likely to remain with us always.

When I was 13, my father gave me my first rifle, a Remington rolling block for the .22 rimfire cartridge. Several months later I saw an advertisement of Lyman sights, and I fitted this rifle with a set. I think I have to thank these sights for my becoming a real rifleman, for with them on this little rifle, I soon became quite a good shot, much better than any of my boy friends, and my interest was maintained and matured, as I do not believe it would have been if I had retained the open rear sight on this rifle.

All through my boyhood years I had a lot of fun and sport with this little rifle, and I shot a lot of stuff with it—English sparrows, squirrels, chipmunks, grouse, and one woodchuck. In 1892, I was lucky enough to win a “Fourth of July” rifle match with it in the Adirondack Mountains, and that year I also shot my first buck with it.

When I was 18, I enlisted in the Pennsylvania National Guard and had no trouble in qualifying as Sharpshooter with the old 45–70 Springfield single-shot rifle, a very sterling, accurate, and reliable arm. The following year I was shooting on my company rifle team, and I also carried this rifle through the first few months of the Spanish-American War until I won my commission. Following that war I “discovered” the magazine Shooting and Fishing, and became much interested in the work of Reuben Harwood with 25-caliber rifles. So I purchased a Stevens No. 44 Ideal single-shot rifle for the 25-20 S.S. cartridge, but it did not seem to shoot nearly as accurately as I was sure I held and aimed it. I know now this was due to the blackpowder factory ammunition which in small calibers never was worth a hoot for accuracy. Anyhow, still following Harwood’s writings, I obtained a Winchester single-shot rifle (low sidewall) for the 25-20 cartridge, with 26-inch, No. 2 half-octagon barrel, pistol grip and shotgun butt, and I placed a gunsling on it. I had John Sidle bush and rechamber this rifle for the 25-21 Stevens cartridge, which was Harwood’s favorite. Sidle also fitted it with his 5-power Snap-Shot scope, which was unique in its day, as it had a much larger field of view than any other scope and was a fine hunting scope for varmints. With this outfit I got much better results but it never entirely satisfied me in accuracy until I had Harry Pope make me a mould for his 80-grain broad base-band bullet, and furnish me with one of his lubricating pumps. Then, with King’s Semi-Smokeless powder the rifle shot as well as I could hold it. I had a lot of fine varmint shooting with this rifle in the hills on either side of the Shenandoah Valley, and when I was ordered to California for station, it proved just the medicine for the Western ground squirrels. For Eastern shooters I will say that these are slightly larger than the gray squirrel, with a shorter and less bushy tail. They live in colonies like prairie dogs and are a great plague to farmers. I disposed of hundreds of them with this little 25-21 rifle. Then, one day, I expressed it to a gunsmith to have some work done on it, and it was lost in transit. I have ever since mourned it.

In the meantime one season I had a chance to go deer shooting in the North Woods and I got a Winchester single-shot rifle for the 38–55 cartridge and had it fitted with a Sidle scope. Sidle was by far our best scope maker in those days. This gun was poorly balanced and too heavy for a handy hunting rifle, but the scope did save me the embarrassment of shooting a cow in mistake for a deer. About this time I also had a Western hunt in view and I got a similar rifle for the 45–70 cartridge, fitted only with Lyman sights. But despite carefully handloaded ammunition it was not as accurate as the old 45–70 Springfield, and I soon disposed of both these rifles.

Then, in 1900, Horace Kephart published in Shooting and Fishing his celebrated article on the use of lead bullets in high-power rifles. He had used a Winchester single-shot rifle for the 30–40 Krag cartridge, and the accuracy he obtained with both jacketed and lead alloy bullets was better than anything I had been able to achieve to that date. So an order went in to Winchester for one of these rifles with a 30-inch Number 3 nickel-steel barrel with .308-inch groove diameter, pistol grip, shotgun butt, and sling. This rifle started a long series of experiments with various loads, methods of resting the rifle, effect of rests on accuracy and location of center of impact, temperature, cleaning, etc., the results of which I gave to riflemen from time to time in the magazine Arms and the Man. A little ignition difficulty was experienced, so I had Niedner fit a Mann-Niedner firing pin, .075 inch in diameter, round headed, with an .055-inch protrusion, and this trouble ceased. This is an absolutely necessary alteration with all our single-shot actions, which were designed in blackpowder days. By this time I had been shooting for several years on the Army Infantry Rifle Team, and I felt quite sure that my results were fairly free from errors of aim and hold. By this time I had also discovered the bench rest.

In 1906, I got a 2 months leave and went on a hunt in British Columbia, taking this 30–40 along as my only rifle. It performed there as well as on the range, and I got mule deer, sheep, and goat with it. One very cold day, in a foot of snow, I came on a band of sheep close to timberline. They evidently caught a glimpse of me for they banded together, and started off, but soon slowed down and resumed feeding. I thought I had spotted a ram in the band, and I monkeyed around them for an hour, by which time I was nearly frozen and had to quit. As I left them, it occurred to me to see if I could unload and load my rifle with my hands badly numbed with cold. I was utterly unable to do so in any reasonable time. To my mind this is the only disadvantage of a single-shot rifle as compared with a repeater. Certainly, the experience of our older sportsmen the world over with good single-shot rifles has been that they can be fired with all the necessary rapidity under normal conditions. However, I must add one other requirement—the single-shot rifle must extract its fired cases easily. Some don’t, due usually to poor chambering or excessive loads.

On a hunt a few days later I came on an enormous rock buttress with two peaks standing up like the ears of a great horned owl. The Chilcotin Indians call this rock “Salina,” which is their name for this owl. On a ledge on the face of the cliff was a big goat. I guess the range was about 500 yards, and I could see no way to get closer, so I lay down and took the shot, holding 2 feet above the goat’s back. Of course I missed that, and two other shots I pulled, and the goat leisurely climbed up and disappeared between the two pinnacles. After a lot of climbing and scrambling, I found my way to the back of this rock mass where it was equally precipitous, and while working around at the base of the cliff I heard something above me, and looking upward I saw the goat or one just like it. At the shot it loosened all holds and, in a shower of small rocks, landed close to me. Then and there I named this rifle “Salina.” I continued to use it as a testing piece for many years, and I also hunted a lot with it in Panama from 1915 to 1917. In 1911, I fitted it with a Winchester 5A scope, and thereafter all my dope was recorded in minutes of angle, from which it was easy to determine elevations, trajectory, and bullet drop.

About this time the NRA was developing interest in outdoor shooting with the smallbore rifle at 50, 100 and 200 yards. Before this scarcely anyone had shot the 22 at longer distances than 25 yards and little was known of the capabilities of the .22 Long Rifle cartridge at longer distances. So I got another Winchester single-shot for this cartridge, with 26-inch No. 3 barrel, set triggers, and sling. I fitted it with my 5A scope and proceeded to give it a good trial at all distances up to 200 yards. I soon found that various makes of ammunition have quite different results in accuracy. With the makes that proved best it would just about group in 2½ inches at 100 yards. This has proved to be about the best that can be expected of this rifle with this cartridge, and this limitation was what finally caused Winchester to develop their celebrated Model 52 rifle for smallbore match shooting. Generally speaking, the old Ballard is the only American single-shot action that has given fine accuracy with the .22 Long Rifle cartridge. However, with this Winchester, I did determine the angles of elevation for all distances, which had not been known or at least never published before I published my table. Also, before I did this shooting, it was not known that there was so much difference in the accuracy of various makes of cartridges in a certain individual rifle.

Following the loss of my old 25-21 rifle by the express company, I had to have another varmint rifle, so I procured still another Winchester single-shot for the 25-20 S. S. cartridge, and proceeded to develop smokeless powder loads for it. I finally found that the best was the 86-grain, soft-point, jacketed bullet with a charge of du Pont Schuetzen powder that filled the case to the base of the bullet. This load shot like nobody’s business, and it gave the finest accuracy up to 200 yards that I had obtained up to that time or heard of anyone else obtaining except with Pope muzzle-breechloading rifles. But my elation was short-lived, for the barrel began to pit, and in less than 500 rounds it was ruined.

About this time we had been devoting much study to the cleaning of rifles. It seemed to us that stronger ammonia was the only satisfactory cleaning solution, so I had a new barrel fitted to this rifle and cleaned it immediately after firing with this ammonia. This did not do a particle of good, and again the barrel was ruined in 500 rounds. The same thing occurred with a Winchester Model 92 rifle for the 25-20 W.C.F. smokeless cartridge of Winchester make. When I wrote them a letter of complaint, they stated that I should not blame the rifle for what was evidently the fault of the powder (which they used)! However, I excuse them for no one knew much about such things in those days. Of course we now know that the old potassium chlorate primer was the devil in the woodshed. With that primer, in small bores like .25 caliber the relatively small charge of powder did not dilute the primer fouling as it did in larger bores like the .30 caliber, and the primer got in its hellish work at once and fast.

For a while there seemed to be no solution for this problem of smokeless powder in small bores. Then, Winchester came out with stainless steel barrels made to order, so I had them build me still another rifle with this barrel, and modeled almost exactly like the fine old 25-21 that I had lost, only it was chambered for the 25-20 W.C.F. repeater cartridge, because I had an idea that the single-shot cartridge would soon be obsolete, which it was. Clyde Baker stocked this rifle, and fitted it with a finger lever that hugged the pistol grip. But before I had time to do much with it, the Kleanbore primer was developed, and this solved all our cleaning and rusting problems. Also at this time the development of the .22 Hornet cartridge shifted our work from the older cartridges to the modern high-intensity types. Later, however, I found that I could obtain splendid results with my 25-20 W.C.F. rifle with a load consisting of the 87-grain, soft point, spitzer bullet made for the 250–3000 Savage cartridge, bullet seated far enough out of the case to touch the lands, and a charge of 11 grains of du Pont No. 4227 powder. The trajectory seems to indicate that the velocity is about 2,000 fps.; evidently, a fine wild turkey load. Of course, the overall length of the load is too great for 25-20 repeater rifles.

Up to this time you will note that I had been using Winchester actions exclusively on all my single shots, both because of their strength and durability, and because they were the only new actions that could be procured at that time. After working for some years with the .22 Hornet cartridge in bolt-action rifles, a friend gave me a good Sharps-Borchardt action, so I had Frank Hyde obtain a 22-caliber Remington high-pressure steel barrel with a 15-inch twist, and fit it to this action and chamber it for the 22–3000 Lovell R2 cartridge. Frank also worked over the firing pin, and made the pin retract with the first down movement of the lever, two very necessary alterations with this action. This rifle, fitted with a 10X Unertl Varmint scope, is a fine, accurate varmint rifle. With good 50-grain bullets and 15.5 grains of 4227 powder it will group reliably, day after day, in about a minute of angle, which is the best that can be expected from this cartridge and a single-shot action.

Occasionally, a five-shot group as small as half an inch turns up at 100 yards, but such is a lucky group. This rifle, however, has one peculiarity. Almost invariably the first shot fired from a clean, cold bore strikes from half an inch to an inch above the succeeding group at 100 yards. I think this is because the groove diameter of the barrel is 0.2235 inch, while all the bullets I have used so far have measured .224. This is no drawback because, knowing it I can allow for it, or can fire a fouling shot before starting on the day’s hunt.

It has quite generally been proven that with equal barrels and loads, a single-shot action will not give as fine accuracy as a modern bolt action. There are apparently only two exceptions, the Ballard action for the .22 Long Rifle cartridge, and the Hauck single-shot action, which is a horse of a different color with its better bedding, ignition, and breeching up. I do not mean to imply that there have not been any single-shot rifles that would give gilt-edge accuracy. There have been quite a few, but I would think that any custom riflemaker who guaranteed to produce a single-shot rifle that would average groups under a minute would soon go broke. So far as we have been able to determine, the difficulties with the single-shot action seem to be in the two-piece stock, the breeching up and the ignition. The single-shot rifle also seems to have a greater jump and barrel vibration than the bolt action. The difference in elevation required between full charges and reduced loads is much greater with it. In this connection it has long been my experience that to get the best accuracy from a single-shot rifle the forearm should not touch the receiver. It should be possible to pass a thin sheet of paper between the two.

The most accurate single-shot rifle that I have owned is one for the 219 Improved Zipper cartridge. I traded Bill Humphrey out of a fine Winchester rifle with 26-inch, No. 3 Diller barrel, .224-inch groove diameter and 16-inch twist, double set triggers, and a fine stock made by him. I had this chambered for the Improved Zipper cartridge with a very perfect reamer made by Red Elliott. This cartridge is simply the 219 Winchester Zipper case fireformed to a 30-degree shoulder angle. You simply fire the factory cartridge in the rifle and it comes out improved. The best load I have found for this rifle has been 32 grains of du Pont No. 3031 powder with the 50-grain Sierra bullet. M.V. is probably around 3,900 fps. After working up this load and sighting in, it gave three five-shot groups at 100 yards measuring .65, .80 and .80 inch. For 3 years, I have used this rifle almost exclusively for all my chuck shooting. Its accuracy and very flat trajectory have given a high percentage of hits at long ranges. With it I made the longest first-shot hit I have ever pulled off on a chuck; difficult to pace because it was up and down hill over rough ground, but it was certainly considerably in excess of 300 yards.

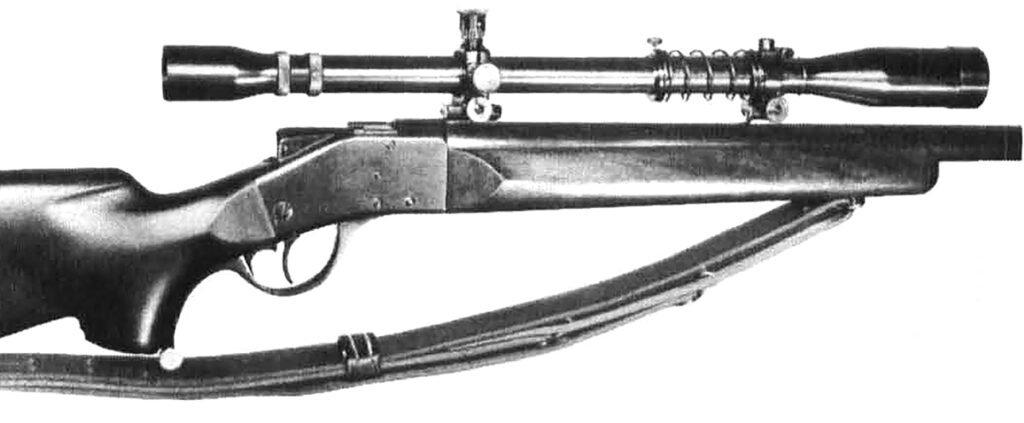

The Stevens No. 44½ action is another on which a most excellent and accurate rifle can be built, particularly for cartridges not to exceed the 219 Donaldson in power. My old friend Jim Garland, who has been my companion on many chuck hunts over the past fifteen years, has a glorious piece built on this action. The Diller barrel was chambered and fitted for the R2 Lovell cartridge, and the lock work done by C. C. Johnson. Bill Humphrey made the stock and the scope is a superb 6X Bear Cub Double. With each lot of cartridges that Jim loads for it, usually with 15.5 grains of 4227 powder, he tests it on the bench, and it has never failed to average under an inch, and with some lots of bullets it gives around ¾ inch. He regards it as his best varmint rifle, and its bag numbers in excess of 300 chucks and hawks. I remember one afternoon 2 years ago when we were separated by a range of hills. Every 2 or 3 minutes I would hear Jim shoot, and toward sundown I wandered over to see what in thunder he had been shooting at. He had a stand on a hill above a creek bottom that was honeycombed with holes, and toward dusk the chucks began to come out. When we went down, we picked up 36 of them shot at distances from 150 to 250 yards. Both Jim and I are rather of the opinion that a first-rate riflemaker will turn out a larger proportion of gilt-edge shooting rifles when he uses the Stevens 44½ action than with any other.

Jim also has a superb engraved Ballard for the 25 Rimfire cartridge, the work of Niedner, Shelhammer and Kornbrath. With Remington or Peters cartridges, it groups the first 10 shots at 50 yards in about ¾ inch, and the second 10 when it is warmed up a little, in about half an inch, and is his favorite squirrel rifle.

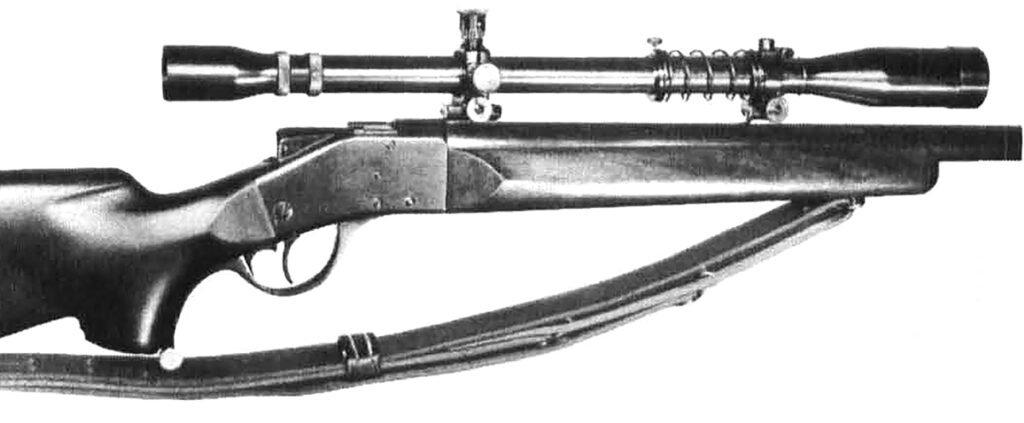

My latest venture in the realm of single shots has been one of the most interesting. Three years ago I took Salina, my old 30–40 Winchester Single Shot, out of the box where it had been in store for several years, well covered in and out with Rig [Editor’s note: Rig is wonderfully effective gun grease, which I have used since childhood], with the intention of trying some new bullets in it. To my consternation, when I put a patch through the bore it came out with red rust and many bodies of big, black ants. Ants had nested in the bore and their acid had ruined it. One day last year, looking at the old piece that had served me so well for half a century, I decided it was entitled to have something done to rejuvenate it. I had on hand a fine 25-caliber Douglas barrel, .257-inch groove diameter and 13-inch twist. So I had H. L. Culver, my metal gunsmith, fit this barrel to the action, and I asked him to chamber it for the Krag case necked down to .25 caliber with a 30-degree shoulder angle. As it turned out, this case is very similar in shape and capacity to the 25 Donaldson Ace. We called it the 25 Culver-Krag. Then, Bill Humphrey made a beautiful new stock and forearm to my exact dimensions, and Mark Stith fitted one of his 4X Bear Cub Double scopes, and I had just about the finest appearing, best balanced and fitting, and steadiest holding rifle I have ever had in my hands. The intention had been to produce an all-around hunting rifle rather than one for varmint or target shooting, and it has turned out to be just that. I have only worked up one load for it so far—the 100-grain Sierra soft point spitzer bullet and 40 grains of 4350 powder. After sighting in I fired five, five-shot groups with it at 100 yards, measuring 1.75, 1.12, .88, 1.85 and 1.98 inches. Before you criticize these groups, consider that they were fired with a rather light-barreled single-shot rifle aimed with a low-power scope having a flat top post reticle, and that the charge was quite a powerful one. It is much more difficult to get a fine grouping with a heavy load than with a light one. Last summer and fall I carried Salina in her new garb for probably a total of 350 miles afoot in my wanderings over the mountains adjacent to my summer home, occasionally gathering in a chuck, crow, hawk or porcupine, and always hoping for a bear or bobcat which never materialized. I have never carried a rifle that seemed as friendly.

All this pernicious activity with single-shot rifles, covering a period of 60 years, started with that rifle in the gun store window when I was a little boy, and that is the way with most of our preference for single shots. It is not their superiority that causes us to select and work with them, but rather some romantic or historic association. An urge to acquire and experiment, not always wise, but usually one that gives deep satisfaction. It seems to many of us that the highly efficient bolt action is but a remodeled musket in a way, that the lever action is a product of America’s unrivaled quantity-production industry, but that the single shot constructed on fine and beautiful lines by a master riflemaker is a gentleman’s piece.

Editor’s note: This article appeared in the 1953 7th Edition of Gun Digest, and, keenly aware that we tread on sacred ground, we have only lightly edited it.

More On Rifles:

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply